Commodore Logo |

Researchers are using the oceans of data in Everquest’s logs for psychological, sociological, anthropological, and other studies. Constance Steinkuehler, a game academic at the University of Wisconsin, has found clear evidence that gamers use the scientific method, experimenting and communicating results, to understand the virtual worlds in which they play.

Academia is finally standing up to take notice of gaming as cultural phenomenon, and Volume 2 of the Journal Transformative Works and Cultures focuses on Games as Transformative Works, dedicating all of the journal articles to various aspects of gaming from a variety of academic perspectives.

Casey O’Donnell’s The everyday lives of video game developers takes an anthropological eye towards the culture of video game developers and their technoscientific art. Rebecca Bryant’s Dungeons & Dragons: The gamers are revolting! explores the fascinating recent history of Wizards of the Coast’s buying the rights to the then waning D&D, making it open-source as a marketing strategy, attempting and failing to revoke the open-license, and finally releasing a new, copyrighted edition of the game and fans hated it. Joe Bisz’z The birth of a community, the death of the win: Player production of the Middle-earth Collectible Card Game explores the life of dedicated gamers after the company producing their game goes under, and makes the most succinct explanation for the appeal of collectible card games, “Though CCG cards are premade, players have the power to edit their own unique deck of 60 cards, a process that can be compared to writing one’s own dramatic television script for an established series.”

I thoroughly enjoyed all of these essays, but Will Brooker’s Maps of many worlds: Remembering computer game fandom in the 1980s resonated with me the most. In it, Brooker describes his experiences revisiting the video games of his youth from the mid 1980s:

I don’t remember Zzoom as a garish clutter of magenta airplanes and bright red tanks, like a kid’s poster painting of a war zone. I remember the way palm trees rushed toward your windscreen in the desert zone, and the way, between attack waves, the camera drifted up into the clouds in a brief, calm interlude. In both cases, I remember landscapes, skies, seas, and natural environments rather than military hardware.

Zork |

Zork and other text-based adventures had no graphics at all, and I spent months adventuring in their dark dungeons and travelling in their fantastic starships. Wasteland was my all-time favorite game on the Commodore 64. It came out in 1986, and, despite being able to push a human-looking icon around on a map, the details of the world were all described in text.

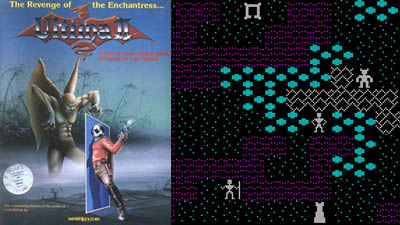

Ultima II Cover VS Actual Game |

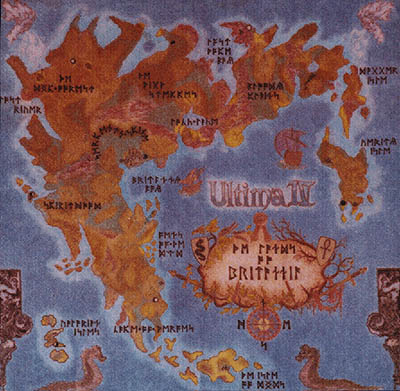

The idea that a screen with stick people could serve as a rich, complex environment may seem silly to today’s gamers, but at the time games like Wasteland, Ultima I-IV, and others provided endless hours of engaging adventure. Brooker observes that these limited in-game graphics were enhanced with elaborate artwork on the box, like the way old arcade games were decorated with action-oriented cartoons to dress up the comparatively simple graphics on the screen. I remember games like the Ultima series coming with cloth maps, code wheels, miniature books, and coins to bring something tangible to the experience.

Ultima IV Map of Britannia |

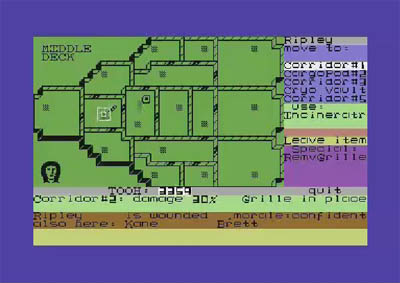

Some games were based on motion pictures, and relied on the player’s experiences watching the movie to enhance the game play. One of the scariest games I ever played on the C64 was Alien, where you must try and kill the alien running around on the ship before it kills all the crewmembers… or failing that, at least make it to the escape pod. Looking at the graphics now makes the fear the game evoked seem silly.

Alien |

Brooker doesn’t fall into the trap of claiming modern games fail to provoke an imaginative response in the player. Rather, he argues that in games like Grand Theft Auto, “I could map my experiences of the simulated spaces—Los Santos, San Fierro, and Las Venturas—onto my memories of the real geography of Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Las Vegas.” So video games are still an imaginative adventure, requiring a suspension of disbelief, or “consensual hallucination” as William Gibson put it. Only the games today have more power to persuade us.

I found a video of someone running through Wasteland in 16 minutes (using cuts and speeded up play). Here’s the first part:

Comments

4 responses to “Gaming Nostalgia”