The ISS photographed from shuttle Discovery in 2006 |

Science Fiction kicks Fantasy’s ass.

That’s the conclusion of this excruciatingly long, flippant, and ostentatious article. So if you are already aware of this fact, you can skip all that follows. If you are one of those elf-ear-wearing, sword-collecting, trilogy-reading, dipsy-doodle fantasy fanatics then please keep reading. As the security guards in my high school used to say whenever they caught me smoking in the boys’ room, “C’mere professor. I need to tell you something about yourself.”

Fantasy sells. Walk into the children’s section of any bookstore and you will find the shelves brimming with works of fantasy, be they Harry Potter, C.S. Lewis, Dragonology, or Eragon. Completely absent are the works of Science Fiction, and the only science that of science fair projects.

Boooooring.

And yet the irony here is that Science Fiction is so much more literary than fantasy. Consider Khan, Captain Kirk’s arch-nemesis from Star Trek II, The Wrath of Khan, despite being driven to incredible heights of over-the-top acting, he still manages to communicate his rage with quotes from Moby Dick, which he eloquently modifies for the space age. Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock quote A Tale of Two Cities, playing literary foils to Khan. Star Trek characters have always shown a love for Shakespeare, and often quote his plays throughout the movies and television episodes. The film Forbidden Planet is a science fiction adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

Consider the crew of the Palamino’s dialogues with the captain of the U.S.S. Cygnus in Disney’s The Black Hole, where even the robot, V.I.N.CENT, cleverly quotes Cicero and aphorisms appropriate to the situation.

Fantasy can’t quote Shakespeare or Moby Dick. They haven’t been written yet. Fantasy can only quote made-up prophecies and the imaginary Necronomicon.

Science fiction heroes and villains often engage in philosophical debates. It isn’t just good versus evil in science fiction, often there is no villain at all, only complex moral conundrums to conquer. Like in the book and two film versions of Stanslaw Lem’s Solaris, where a psychologist is reunited with his late wife, but its not really her, only an amalgam of his memories of her. An intense psychological drama of man versus himself develops, and we can’t help speculating on it long after the story is told.

Fantasy’s challenges are pretty shallow in comparison. Golumn wants the ring. The witch wants to rule Narnia. The hero needs to overcome fear and become a leader. Such simplistic storytelling leads to simplistic worldviews.

Science fiction has depth; it challenges its audience to think, and that is why people steer clear of it. It’s complex, and people just don’t get it. Audiences want simplicity, so they go for the brainless clear-cut good versus evil themes fantasy has to offer.

This is why I can’t find a single movie theater showing the film Sunshine within a 100 mile radius. This is why I had to spend hours explaining films like A.I., 2001, and Ghost in the Shell II to people who thought they were just dumb and boring. We live in a world that’s growing more complicated by the moment, accelerating toward the singularity, but most people want to just tune out and forget about it with shallow diversions.

All is not lost, however, as science fiction’s depth excels on the small screen. Lost and Battlestar Galactica are two of the most critically acclaimed shows at present. Star Trek held a faithful audience for decades. There are people who want challenging content. It’s just getting everyone else to see the beauty in SF that’s the problem.

Fantasy is stoopid. Science Fiction enlightens. More on this to follow over the next few weeks.

Disclaimer: Although still fantasy, I would like to acknowledge that the Harry Potter series of books have certainly advanced fantasy to a much more complex level of drama, with characters who actually have very long histories and deep emotional and philosophical motivations–still not as cool as SF though.

Fantasy’s Monarchy VS SF’s Democracy

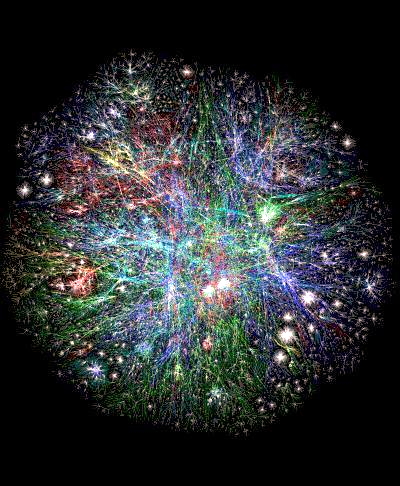

Author William Gibson predicted the Internet and the Age of Amateurs in his Neuromancer books. |

The LOTR stories are about “chosen ones,” a common theme in fantasy stories, be they kings, hobbits, or wizards. Only these elites, born into their statuses, may save the world.

It’s also really boring. Here’s every single “chosen one” story line:

Someguy: I think he is the chosen one!

Choosen One: But I’m just some doofy pud-wacker!

Everybody Else: He is the chosen one!!!

The Grand Poo-Bah: He has defeated the melodramatic personification of pure concentrated evil!!! Thus, proving his status as the chosen one!!!

Everybody: Hooray for the chosen one! Let’s party!

Chosen One: Hooray for me!

There, now you can skip seeing Lord of the Rings, The Matrix, Star Wars, Eragon, Harry Potter, Willow, Highlander, Dragonslayer, Flash Gordon, Transformers The Movie, The Golden compass, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, The Neverending Story, Dune, Legend, Excalibur, and the New Testament.

If you weren’t born with “metachlorians” in your blood, a magical birthmark, or a fair complexion, blonde hair, blue eyes, and a penus, then I’m sorry, but you don’t qualify as a chosen one, and no amount of body building, martial arts training, plastic surgery, motivational speakers, higher education, psychotherapy, hard work or determination will every make you the chosen one.

Chosen ones are chosen ones because they are chosen. Got it? Some prophecy or forshadowed chain of chance sets them up as heroes, and the lesson here is that, unless you are a chosen one, don’t bother trying to be heroic. It’s completely out of your hands.

The best you can hope for is to die in the chosen one’s service. But it’s not all bad. Who knows, may maybe the chosen one will be inspired to avenge your death! Or maybe he’ll watch the light fade from your eyes and realize what horrible fate awaits everyone if he doesn’t get his act together, kill the evil one, and claim his kingly birthright.

What is a king anyway, but a social parasite? America was founded on a rebellion against kings appointed by god to rule over us. Monty Python and the Holy Grail has a fantastic response to the annointed ones, as a peasant informs King Arthur, “Strange women lying in ponds distributing swords is no basis for a system of government.” The human race has evolved past fantasy’s antiquated totalitarian social systems, so why waste our money and time on a genre that romanticizes such injustice?

Now compare this with Star Trek, where a team of experts regularly collaborate on problem solving. Star Trek heroes are heroic because they went to Starfleet Academy. They study in their spare time to keep on top of the latest advances in their fields. They are perpetually exploring and broadening their horizons to become better heroes, and anyone, even the audience, can do the same. The film Trekkies catalogues Star Trek fans, most of whom are scientists, doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who were inspired to their careers from Star Trek’s vision.

Fantasy’s heroes wield swords, and oftentimes come from backgrounds such as farmer, rogue, or knight. There’s plenty of good eats in fantasy realms, but they never explain where any of it comes from, except for Harry Potter, where food just magically appears. Fantasy realms synch very well with modern mass-consumerism, where the goals are to horde as much treasure, magic items, and weapons as possible while consuming great big feasts at every inn and castle on the way.

The logistics of where food comes from and how the market functions are details often covered in SF, whether its teraforming planets like Mars, hauling goods like the crew in Alien, or just exploring to expand human knowledge. In SF worlds where technology has made resources nearly apparently infinitely plentiful, like that of Star Trek, it is emphasized that society has evolved to a post-modern state where personal improvement has replaced material wealth as life’s focus. Science Fiction heroes are psychologists, astronauts, chemists, physicists, and explorers. Science Fiction heroes have real world careers we can all pursue in the present.

In SF, heroism is open to everyone.

Fantasy’s 2-D VS SF’s n-D

Space Colony design for NASA Image by Donald Davis |

Fantasy doesn’t explore the philosophical differences between its villains and heroes, not because there aren’t any, but because those differences are so simplistic that debating them would only emphasize how undeveloped the characters’ motivations actually are.

Why does the villain want to rule with an iron fist? Is it because he got wedgies from the good-guys as a child? Is it because he read Mein Kampf, and was inspired by Hitler’s rhetoric? Did he play too many violent video games?

No. The villain is a bad guy because he’s bad. The hero’s a good guy because he’s good. They don’t like each other because bad and good are opposites, so they must fight epic battles. It’s the sort of simplistic, reductionist crap most of us worked through in the sandbox as children, but fantasy still grapples with as if it were the eternal question: Is it better to be good or bad? Oh! I just can’t wait till the end of the story to find out!!!

A lot of Republican rhetoric appeals to fantasy dorks.

Science Fiction has lots of eternal questions, and they’re all much more thought provoking. Star Trek tries to come up with one complex ethical dilemma every episode, meaning 736 ethical dilemmas to grapple with so far.

What does it mean to be human? is one of the great questions Science Fiction meditates on all the time. Roy Batty, leader of the renegade replicants in the film Bladerunner, plots murderous revenge against his creators, but takes a different strategy against Decker, the mercenary hired to hunt him down and kill him. Roy toys with Decker in the film’s climax, terrorizing him, and then unexpectedly saves his life. All of this to demonstrate the point that Roy, despite being an engineered being, still deserves the respect afforded any human.

Planet of the Apes explores this philosophical debate in greater detail. In fact, most of the film is one human trying to win human rights in a society of advanced primates. George Taylor, played by Charlton Heston, debates civil rights with Dr. Zaius, demanding simian rights for humans in a world where apes rule and humans are primitive animals. The film also pits science against religion as Dr. Zaius’ religious dogmatism prompts him to perpetually ridicule Doctors Zira and Cornelius for studying humans and trying to domesticate them:

Experimental brain surgery on these creatures is one thing, and I’m all in favor of it. But your behavior studies are another matter. To suggest that we can learn anything about the simian nature from a study of man is sheer nonsense. Why, man is a nuisance. He eats up his food supply in the forest, then migrates to our green belts and ravages our crops. The sooner he is exterminated, the better. It’s a question of simian survival.

Dr. Zaius, the audience comes to learn, has some very complex and profound reasons to fear scientific progress, and the film’s ending, which seems to justify his prejudice, leaves us wrestling with questions about our moral choices as a species.

Dr. Zaius from Planet of the Apes, V.I.K.I. from I, Robot, Reinhardt from The Black Hole, the Architects from The Matrix, Magneto from the X-Men, Dr. Frankenstein or his monster, the replicants from Bladrunner, Coffey from The Abyss, Dr. Octavius from Spider-man, and just about every single Star Trek antagonist are not wholly good or wholly evil, but complexly human and misguided. Understanding their motivations can be a challenging experience for the audience.

And these human antagonists are merely a drop in the bucket of conflicts SF poses to its audience. There are also the many “man versus nature” stories in SF, like Solaris, Foundation, Mission to Mars, Red Planet, Alien, The Core, Deep Impact, Armageddon, The Abyss, Voyage to the Center of the Earth, The Andromeda Strain, and Fantastic Voyage. Even the Martians from War of the Worlds are a sort of natural threat, an incomprehensibly alien species motivated by the need to acquire basic resources for survival.

“Man versus nature” conflicts are restricted to merely adding flavor to fantasy stories, as characters must climb mountains, fight monsters, and travel long distances. “Man versus nature” would completely fail as the central plot for a fantasy story, because it would so completely lack any connection to real life that people would not be able to engage it emotionally. Without bad guys, fantasy becomes so irrelevant that even fantasy fans would abandon it.

SF’s Futurism VS Fantasy’s Golden Ageism

Instead of Becoming Dated, Films Like Bladerunner have only become more relevant. |

In Star Trek human beings are the aliens, traveling through space in a type of flying saucer and secretly visiting primitive civilizations like the one we live in presently, never interfering with them so as not to violate the “Prime Directive.” Star Trek provides a powerfully positive vision of what the human race may become with ambition, scientific understanding, and technological progress.

Conan, The Barbarian is about a barbarian. He travels around a teensy-weensy percentage of planet Earth’s total landmass, chopping things with his sword, and seeking revenge against the man who killed his parents. Conan presents a fairly powerful glimpse into a single lifetime from ancient human history, but one we may only experience if we abandon all technology, burn down all libraries and universities, revert to a monarchic model of government, and stop wiping our butts.

I love Star Trek. Star Trek inspires me to educate and improve myself. I know I can’t achieve in my lifetime what Star Trek presents, but I also know my children’s children’s children will one day make similarly fantastic accomplishments, so long as they remain as inspired as I am by SF’s vision.

At the same time, Conan, while entertaining, doesn’t provide a practical model for inspiring present-day activity. I like having a clean butt, and I want my children to have clean butts; therefore, Conan doesn’t hold much appeal as an idol for admiration. The LOTR films were entertaining, but we all know the reality is that Frodo would be missing lots of teeth, Gandalf would be a very stinky old man, and Aragorn would have a serious flea problem.

Science Fiction looks upwards and outwards to the future, while Fantasy broods on an overly idealized dramatization of the past. Fantasy wants to delude us into thinking things were better, more exciting and morally clear in mythical ancient times without electricity and running water. Science Fiction argues that the best times lay ahead of us, but only if we make them happen. L. Ron Hubbard put it best, when he said:

[science fiction] is the herald of possibility. It is the plea that someone should work on the future. Yet it is not prophecy. It is the dream that precedes the dawn when the inventor or scientist awakens and goes to his books or his lab saying, “I wonder whether I could make that dream come true in the world of real science.”

Some science fiction stories are positive about the future, while others are cautionary. Soylent Green, aside from it’s very mediocre plot twist, very accurately portrays a dying Earth, where bicycle generators are used to charge batteries for reading lights and televisions, where civil unrest spurned by scarce resources causes riots, where overpopulation has stripped the Earth bare so all that remains is suffering and decent into chaos as the human race goes extinct.

It’s possible that fantasy stories are a possible future, taking place a few million years after some catastrophe wipes out civilization. Through divergent evolution ogres, trolls, hobbits, giants, and other monsters spring up throughout the world. The magical rings, staffs, and wands are actually ancient technologies left over from civilization’s technological peak. Arthur C. Clark said that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic after all. Maybe the Lord of the Rings is a cautionary tale, about how if we don’t preserve civilization and scientific progress we’ll end up fighting disembodied eyeballs and mutant hordes?

That still wouldn’t make it SF. Even Science Fiction’s post-apocalyptic tales look forward to progress. The Postman deals with rebuilding civilization after a catastrophic collapse of its social structures. Foundation deals with preserving science and technology, spreading their benefits across the galaxy after the empire collapses. The apocalypse is never the end in SF realms; more often it is merely the beginning.

Star Trek‘s positive vision is an entirely possible future for the human race, unless the Fantasy dorks are allowed to hold civilization’s progress back with their silly romanticism. I don’t mean that fantasy dorks are going to proactively regress civilization back to a point where everyone is lice-infested and stinky-butted; but fantasy dorks, through the intense apathy their genre affects in its fans, will act as anchors to human progress through their day-dreaming and antipathy.

So I’m asking the fantasy dorks to think about it, really think about it: Would you actually want to give up your microwaves, hot water, soap, dental hygiene, extended lifespans, automobiles, airplanes, Internet, fast food, clean butts, LOTR video games and action figures so you could be one of those ants fighting ogres on the battlefield in some epic clash between good and evil?

SF’s Plausability VS Fantasy’s deus ex machina

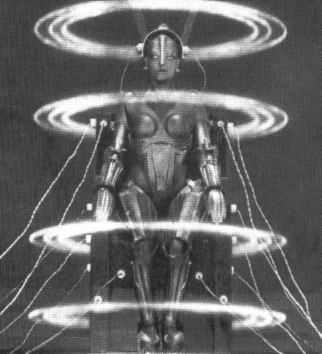

As far back as 1927 SF films like Metropolis were predicting robotics. |

In Lord of the Rings the wise old man sends some hobbits off to throw a ring in a volcano to slay the evil one. In Krull the wise old man guides the prince to find the magic ninja star, the only weapon capable of slaying the beast. In Dragonslayer the hero must throw the wise old man’s ashes in a lake of fire in order to resurect him so that when the dragon seizes the wise old man, the hero can smash the amulet, blow up the old man, and take the dragon with him. In Monty Python’s Holy Grail the king must lob the Holy Hand-Grenade at the man-eating bunny rabbit on his quest for the grail–okay, that was pretty cool.

In Science Fiction, solutions usually have to make sense if the writer is worth a damn. In The Terminator, Sarah Connor has to burn away all of the robot’s skin, blow it in half with dynamite, and crush it in a compactor according to the laws of physics and explody-type-things.

In Terminator 2: Judgement Day, the T-1000 is amorphous, so we don’t know how they’re gonna stop it until they push it into the vat of molten steel, and then the audience gets to go “Hooray!” for real, because the solution makes logical sense. There was no pre-defined quest for a magical ring, there was all the laws of nature we deal with everyday, and the characters figured it out creatively.

In War of the Worlds, the humans have no hope of defeating the vastly technologically superior Martian invaders; however, nature steps in to save the day, as the Martians have not evolved immune-system responses to Earth’s indigenous bacteria and viruses. The resolution is satisfying because of its scientific plausibility.

In fantasy films invincible monsters like vampires, werewolves, and dragons are totally undefeatable unless our hero can find the chink in the armor, the magic item, or other deus ex machina set piece that will defeat it for reasons the writer doesn’t have to explain because it’s fantasy, you just make the $#!@ up as you go along.

Fantasy is just lying uncreatively.

Now, admittedly, science fiction is not immune to the deus ex machina magical solution either. Anyone who’s seen a few episodes has been exposed to Star Trek’s “treknobabble,” which crosses the line from Science Fiction to Fantasy:

Red Shirt: We’re trapped in temporal anomaly!

Engineer/Science/Etc Officer: Captain, I believe if we stimulate the ship’s positronic matrix to generate a gamma-burst of sub-space ipso-facto metaneutrinos it should destabilize the anomaly long enough for us to break free.

Captain: You’re just making that up, aren’t you?

Actually, the Captain would nod his or her head sagely and say “Make it so,” and then the Technical Officer would push some blinky-lights or wave some blinky-instrument over something blinky and all would be right with the world–except for the audience’s suspension of disbelief.

Most horror films are fantasy. Silver bullets and crosses dispatch werewolves and vampires without any logical reasoning. All Zombie movies are fantasy, even the ones that try to rationalize walking corpses as being the result of some virus or secret government experiment gone awry. Only the film 28 Days Later works as a Science Fiction zombie flick, because the people infected with the rage virus are still living, and eventually starve to death.

There are a few horror films that are science fiction. Alien and Aliens are both hard-core science fiction horror flicks. In the Alien movies, there are many doctors, scientists, and space-marines dissecting the monsters, trying to figure out how they tick and how they behave, so they can win the fight.

Could you imagine a character in a fantasy story stopping to dissect a troll, ogre, dragon, or unicorn? Of course not! That’s because all fantasy monsters are filled with straw, there’s no need for them to be filled with anything else.

Plausible details are just one more thing separating SF from Fantasy. Hard SF audiences expect details. They want to know the physics behind the Enterprise’s warp drive, the cloning process for the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, the evolutionary history of simian dominance in Planet of the Apes, the endless technological specifics of the message from an alien civilization in Contact, and the myriad requirements for landing on our next most promising human adventure in Mission to Mars and Red Planet.

In fantasy, all these things are just magic.

Fantasy’s Teeny Realm VS SF’s Cosmic Proportions

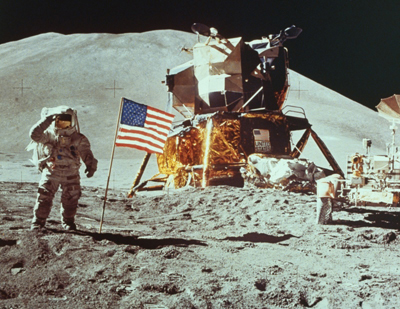

An Image impossible in Fantasy. |

The Lord of the Rings felt like an incredible epic. The characters travel across vast plains, climb mountains, and visit faraway lands. The battles involved hundreds of thousands of soldiers and monsters wielding massive armaments and siege machines. Flying lizards, giant spiders, and demonic hordes filled in the fantastic sceneries of a world with an ancient and equally epic history.

And that pales in comparison to the scope of Science Fiction.

The characters in every single one of Terry Brooks’ Shannara novels traveled hundreds of miles described in such excruciating detail that the reader has to wade through what the characters ate, the weather, the types of grass, and so many other boring minutiae for hundreds of pages until they finally get to the ultimate battle between good and evil.

Yawn. The characters in Red Planet traveled 48 million miles to Mars. Those in 2001 traveled 369 million miles to Jupiter. Characters in Asimov’s Foundation books travel light-years all over the Milky Way galaxy in routine manner. It’s amazing what characters may accomplish when they don’t have to walk everywhere.

Gandalf fought the Balrog all the way down a really deep hole and then all the way back up to a tall mountain!

Big whoop. The adventurers in The Core traveled to the very center of the Earth, fighting technological, natural, and human hazards all the way down and all the way back up to the Earth’s crust again. Characters in Fantastic Voyage and Innerspace fought their way all through the human body’s many systems and all the hazards that come with them.

It’s common practice in fantasy novels to have a two-page map of the realm in which the characters are venturing to impress upon us just how epic is the world in which the action is taking place. Amazing, huh?

Not! Science fiction movies have satellite shots of Earth. The film Contact opens with a shot of Earth and pulls away, out of the solar system, out of the galaxy, and out to a view of many galaxies. The film Men in Black pulls out from Earth, past many galaxies, and out to many universes. In fantasy, the highest we can climb is the eagle-eye view. That’s because, in fantasy, the world is flat.

The Dragon Riders in Eragon spent thousands of years protecting and guarding and stuff.

How retarded! The film A.I. begins in our near future and then jumps 10,000 years ahead of that. And you know what else? Things changed in that amount of time. Technology advanced incomprehensibly, society changed, its inhabitants were different, and in so many ways things had improved. Compare this to a bunch of dumbass Dragon Riders who never updated their swords to guns or dragons to fighter jets despite having millenia to do so.

The Balrog, Godzilla, and Dragons are really big. That’s got to count for something.

Hardly. V’ger, from Star Trek, The Motion Picture, is so large that much of the movie is spent showing the Enterprise traveling through it. Its mind is so large that Spock can go exploring in it and find complete replications of all its travels. The living ocean in Solaris covers an entire planet. Colossal SF beings, unlike Fantasy’s, have much bigger interests and aspirations than world-domination. V’ger wants to find god. Solaris is so advanced we cannot even decipher it’s motivations.

There were thousands of monsters and people on Lord of the Rings’ battlefields. When Sauron is destroyed a volcano erupts and the earth swallows its legions of monsters. Isn’t that impressive?

(Rolling eyes and pantomiming masturbation.) War of the Worlds and Independence Day both reduced entire cities to rubble. Star Wars blew up entire planets. 2010 turned Jupiter into a star to thaw out life on Europa and accelerate its evolution.

About the only place fantasy might have an edge over SF is on the subject of immortality. There are a lot of eternal characters in fantasy. Immortal bad guys and immortal good guys that have always been around doing their epic immortal stuff, and at the end of the story, they will continue with their immortality, either in a state of eternal punishment or eternal bliss.

SF has its immortals, but “Happily ever after” is nothing but a curse in most SF tales. In LOTR Arwen Evenstar’s father warns her that, as an immortal, if she abandons her elfin people, her mortal lover will eventually die and she will be alone forever. In Science Fiction, all of the immortal elves would be cursed, as eventually the Universe would dissipate to an entropic state of absolute zero, leaving them frozen in total darkness forever. In SF, it sucks to be an elf.

It is the fact that people do not have all the time in the world to accomplish things that motivates their ambitions. Often in SF, immortality is a form of stasis, devoid of emotional, intellectual, or spiritual growth–sort of like sitting through all 16-plus hours of the extended DVD version of Lord of the Rings.

Face it fanboys: Science Fiction has a significantly larger phallus than fantasy.

Fantasy’s Escapism VS SF’s Engagement

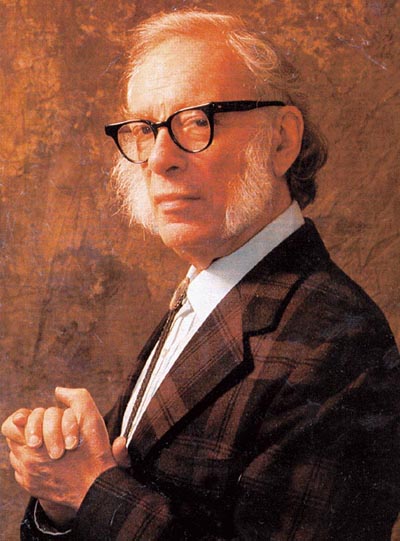

Isaac Asimov |

Fantasy is about taking all our present media technology, CGI-special effects, billion dollar movie industry, and creative potential, and using all of it to pretend that none of it exists. Fantasy runs away from our incredible reality with its tail between its legs to cower in romantically-reenvisioned supposedly simpler times.

C.S. Lewis (Chronicles of Narnia) and J.R.R. Tolkien (Lord of the Rings) were English faculty at Oxford. Terry Brooks (Shannara series) has a JD and BA in English Literature. Robert Jordan (Wheel of Time) has a BS in Physics. J.K. Rowling (Harry Potter series) has a BA in French. Christopher Paolini (Eragon) has no higher education as of yet.

David Brin has a Ph.D. in Space Science. Stanislaw Lem could not attain his medical degree because he refused to accept Lysenkoism, but did work as a scientific researcher. Robert Forward, Gregory Benford, Charles Sheffield, Vernor Vinge, Hal Clement, Joe Haldeman, Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle and Stephen Baxter are all distinguished working scientists and contributors to the philosophy of science.

Dr. Isaac Asimov was a professor of biochemistry, Vice President of Mensa International, and president of the American Humanist Association. He didn’t just write engaging stories about possible futures and speculative science, he also wrote hundreds of books on present-day science, politics, and human improvability.

Science Fiction authors have often accurately predicted the future from cell phones to the Internet. They have contributed to the human race’s collective body of knowledge, and they have inspired countless others to do the same.

What have fantasy writers accomplished? They’ve made money. They’ve inspired countless others to stand in long lines at movie theaters and books stores sporting capes, brandishing light-sabers, wearing all-black, and debating what trilogy from what series is the best based on purely subjective criteria.

Fanboys are impotent slaves, mentally masturbating to fantasy’s sound and fury. All they have to look forward to is bigger swords, flashier magic, and more gruesome monsters. Fantasy is an intellectual dead end.

SF fans are intellectually engaged with their subject matter, taking the speculation beyond what is presented, and internalizing its vision to inspire their own accomplishments and contributions to society. SF walks alongside civilization, evolving and growing in potential as we grow and evolve as a society and a species.

Fantasy will always remain a fun way to burn a few hours relaxing with its eye-candy, role-playing, or adventure books; however, Science Fiction will always complement its entertainment value with a substantial dose of practical philosophy, speculation, possibility, and human potential.

Comments

2 responses to “Science Fiction VS Fantasy”