At one end of the spectrum are the religionists, who believe the human race was created above the animal kingdom, distinct from it. Animals have nothing in common with human beings other than the relationship of being at our subjugation. At the other end of the spectrum are environmentalists who see animals as equals to human beings, no matter how rudimentary their cognitive capabilities, and they hold this position with a religious fanaticism.

Anthropomorphism

We tend to project ourselves onto the world around us. We are egocentric. Evolutionarily it makes sense to be most concerned with ourselves and to therefore watch the world as it relates to us.

Pro-Life advocates anthropomorphize the heartbeat of a developing fetus into a fully developed human being. PETA anthropomorphized chickens in stocks with prisoners at Auswitch. Children anthropomorphize dolls and action figures into real human beings.

Another extreme is pets. We project motives and character onto our animal friends. We believe they are intuitive, sneaky, conniving with levels of cognitive complexity of which they are incapable.

Many of us even anthropomorphize the Earth into a living being. “Mother Earth” and “Mother Nature” are two terms that take the complex interactions of our shared biosphere and create a metaphor for a collective living being out of them.

All of us anthropomorphize inanimate objects in our world. We refer to cars and ships as “she,” and even use attitude descriptors to characterize their behaviors. “The computer refused to accept the command,” is one example. In the field of logic, this is known as the Pathetic Fallacy, but there are cases where we try so hard not to anthropomorphize that we miss the obvious similarities between ourselves and the world around us.

Anthropodenial

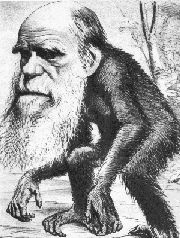

B.M. de Waal coined this term, and throughout history, people have sought to definitively raise human beings above all other forms of life. It is important for us to feel special as a race, held above the rest of life on Earth as if on a pedestal. Many people find the very notion of being lumped in with the rest of the animal kingdom outright offensive. We merely need to look at the history of our public discourse on evolution to find evidence of such revulsion. The cartoon depicted here of Darwin as a monkey was inspired by such outrage at the notion of primate ancestors.

B.M. de Waal coined this term, and throughout history, people have sought to definitively raise human beings above all other forms of life. It is important for us to feel special as a race, held above the rest of life on Earth as if on a pedestal. Many people find the very notion of being lumped in with the rest of the animal kingdom outright offensive. We merely need to look at the history of our public discourse on evolution to find evidence of such revulsion. The cartoon depicted here of Darwin as a monkey was inspired by such outrage at the notion of primate ancestors.

It is no wonder then that so many rationalizations exist to erect a wall of reason separating the human race from all other species. “Beasts abstract not,” John Locke said, attempting to distinguish humans from animals through what he and most others believed a uniquely human cognitive capability.

The Anthropodenialists reject the parrot, N’kisi, who has a 950 word vocabulary and has demonstrated the ability to combine words in new ways so as to describe new things. The famous chimpanzees Washoe, Lucy, and Lana, each had between a 100 and 200 word vocabulary in sign language and written word.

Buy why should we even go to such extremes in the animal kingdom to make the point that animals share more with us cognitively than many care to admit? When a pet cat purrs or a dog becomes excited in our presence, what are we doing to ourselves when we write these emotional exhibitions off as purely instinctual?

We are forced to consider our own emotional reactions as mere programming, and that begins a slippery slope. Denial taken to an extreme can begin to exclude other humans. Eugenicists throughout history have always sought such rationalizations for their egocentric ideologies. After humans separate themselves from the animal kingdom, the next step is for cultures to begin distinguishing themselves.

Bishop Berkely had a response to Locke’s above comment, “If the fact that brutes abstract not be made the distinguishing property of that sort of animal, I fear a great many of those that pass for men must be reckoned into their number.”

What is Human?

If Chimpanzees and parrots have the ability to abstract, if gorillas and other primates have culture, then what makes humans special is merely the level of sophistication in which we exhibit these traits. What is a human becomes a question of degree.

Likewise, the conclusions we draw about how we should interact with our world rely on this subjective notion. Personally, I try not to eat beef because I see cattle as having sufficient cognitive capabilities to perceive their slaughter as cruel. At the same time I have no problem eating chicken and fish because their relatively rudimentary cognition.

Both anthropomorphism and anthropodenial are characteristics of our egocentrism, either by seeking ourselves in our surroundings or by distinguishing ourselves from them. Like all false dichotomies, either extreme is simply wrong; therefore, a perpetual disputation supplemented with persistent inquiry is required to find the ideal mean between excesses.

Further Reading:

“The Dragons of Eden,” Carl Sagan, 1977, Ballantine Books.

Comments

One response to “Anthropomorphism VS Anthropodenial”

[…] Not to get too anthropomorphic about animal behavior, but humans and pinnipeds are both social animals. We may be able to learn some lessons about our own social behaviors by watching the sea lions. Anthropomorphism, or the projection of human characteristics and emotions to the animal world has been criticized by some for a long time, especially by those who view humans as superior to other life forms. However, primatologist Frans De Waal coined the term “Anthropodenial,” which is a blindness to human characteristics of other animals. According to an article in 2005, “There are cases where we try so hard not to Anthropomorphize, that we miss the obvious similarities to the world around us.” (https://ideonexus.com/2005/11/09/anthropomorphism-vs-anthropodenial” […]