In his book Chess Metaphors, about chess, neuroscience, and artificial intelligence, Diego Rasskin-Gutman devotes a short section to the popular myths, literature, and films dealing with characters creating artificial humans from motivations like desire, necessity, curiosity, and power. More fascinating than the motivations for producing AIs, is the evolving origins of where the artificial life comes from in fiction:

8 AD

One of the myths retold in Ovid’s Metamorphoses is of King Pygmalion who, when he grows disenchanted with real women, sculpts a statue of a woman with whom he falls in love. The Goddess Venus brought the statue to life in response to Pygmalion’s prayers, and the King married her. There were other examples of artificial life in Greek mythology, but this is the most compelling throughout the following millennia, inspiring numerous works of art, including George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 play Pygmalion, which was later remade as the 1956 musical My Fair Lady

1800s

As the legend goes, the 16th century rabbi of Prague Judah Loew ben Bezalel created a Golem out of clay or soil, bringing it to life with the word “emet” on its forehead. When the Golem had terrorized those prosecuting the Jews sufficiently to have them relent, the rabbi killed his creation by erasing the letter “e” from its forehead, leaving “met,” Hebrew for “death.” Although there is divine intervention involved in the creation of this artificial being, everything is under the rabbi’s control.

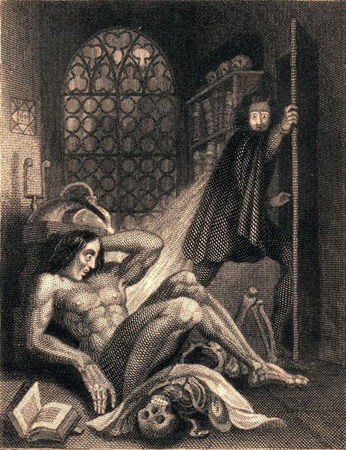

1818

A story of artificial life without anything divine in its origin’s is Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, where Dr. Frankenstein fashions “the monster” using ambiguous means; however, Dr. Frankenstein’s background in chemistry and other sciences certainly contributed to his success in creating life. The monster is an outcast, abandoned by the fearful doctor and alienated from other people due to his frightful appearance. So a second trend appears in the myths of artificial life, that the more involved a human is in the creation of life, the more inhuman that life becomes.

1921 and 1927

This trending of artificial life into malevolence continues with Karel Capek’s play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), where artificial humans, mass produced at a factory, revolt and drive the human race to extinction. The Machine from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis also serves as a cautionary tale, engineered by Doctor Rotwang, the robot impersonates the leader of the workers and uses their trust to inspire a revolt. In the first example, the artificials use their overwhelming numbers to overthrow humanity, in the second, a single artificial uses its resemblance to humanity to manipulate it. The robots grow increasingly insidious as they grow powerful.

2001

Although not in Rasskin-Gutman’s examples, the robots in the film Artificial Intelligence: A.I both blend in with humanity and are mass-produced; however, Spielberg and Kubrick’s future AIs are highly benevolent beings, curious and generous. They lament the extinction of the human race that we brought upon ourselves, and try to understand us by resurrecting humans out of space-time. Although this new myth has yet to withstand a few decades of time to see if its message will stick in cultural memory, it does signal a new direction for human perceptions of artificial life, from divine gifts, to manufactured monsters, and now manufactured gods. “The secret of life is sought in a gradient of divine intervention to human intervention, which is also a temporal gradient,” Rasskin-Gutman notes, “representing the triumph of science over religion.”