|

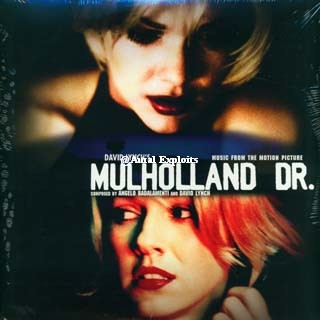

Let me begin by warning anyone who intends to see this movie that it does not make any sense. It seems like it will make sense. There’s a plot, there are fantastically effective scenes, great characters, all the components of a great movie… minus a coherent conclusion, and yet Mullholland Drive is David Lynch’s most accessible film, filled with all the bizarre characters, nightmares, and wild dramatic moments that are the trademarks of his work.

The plot, or what appears to be the plot begins with Rita, about to be murdered, but saved by a car accident. She stumbles away in an amnesiatic state and ends up at Betty’s aunt’s home. Betty is staying there while she tries out for parts in Hollywood movies, and she decides to help Rita figure out her identity. Running parallel to this storyline is Adam, a director who’s film is being taken over by the mob. They are demanding he recast the lead actress in his film with their own, and until he does so, they will keep the production shut down.

David Lynch is a master of scenes. He has created some of the most intense moments in cinematic history and contrasted them with moments of beauty to make the audience cry with relief. Adam’s meeting with the mobsters concerning his choice of leading ladies, Betty’s two completely different performances of the same dialogue for her tryout, the Cowboy’s dialogue with Adam on the ranch, and the stage performance at the Silencio Club are all incredible scenes. There are more, smaller scenes, all significant unto themselves, however much we ponder their contribution to the whole.

Naomi Watts, the lead actress, has run the gauntlet in this film. She not only completely switches her character’s personality partway through the movie, but give two drastically different mini-performances of a single scene, illustrating how different the actor’s delivery can make it. In an interview, she talked about how difficult it was to make a scene where her character masturbates while crying, simultaneously disturbing us and evoking sympathy.

The power of Watts’ performance further illustrates the film’s central theme of identity. One character who has lost her identity, another with the ability to become any. Who is the real person, Betty or Diane? Rita or Camille? The film’s setting, Hollywood, emphasizes this theme. A world of illusions, recordings, death pretending at life, denial. Silencio.

The film is profuse with clues hinting at something solid and coherent below the confusion at its surface. The cowboy’s statement about being seen once versus being seen twice. For one person, he appears twice, for another, he appears once. Then there are the malicious supernatural beings, the old laughing couple, and the monster behind the diner. There is the blue box, the key, memories or reality? The stage performance where a woman continues to sing although she has expired? The waitress at the diner’s nametag and its significance? The closing credits dedicate the film to Jennifer Syme? Silencio.

Each viewing reveals more clues, more connections. A web of settings seem to tie the mobsters to Betty. Like dots begging to be connected: the cappuccinos, the people, the places, the names, the purse with the money, the limo, all of these dots on the page and our minds seeking to explain them. So many juxtapositions of details, each viewing revealing more. Silencio.

Do they mean anything? I have a hypothesis, and my friends have different ones. Draw your own conclusions, but I guarantee your mind will churn trying to put them all together. Beyond the film’s emotional power, its entertainment value, and its incredible performances, it is its ability to make us think in circles that makes it experimental, daring, and fantastic.

See Also: Jacob’s Ladder, The Lost Highway