In 2003 DARPA was researching the potential of a prediction market to guide policy in defense against terrorism. Called FutureMAP, the program was abandoned under heavy criticism from Congress, which percieved the program as people gambling on the odds of a terror attack. There were many policies to criticize in the War on Terror, but I don’t believe this was one of them.

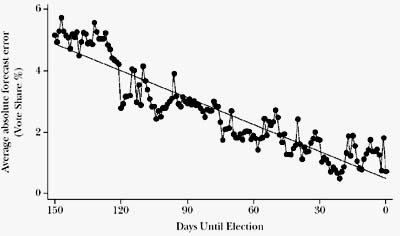

Increasing Accuracy of Prediction Market in Days Approaching Election |

Prediction Markets are a useful and important new tool that harness the wisdom of crowds. In Bayesian Epistemology, they are known as Dutch Book Arguments, where individuals not only make predictions of events, but place monetary wagers on them. Literally putting their money where their mouth is. Imagine, not only all the money that could have gone into critics bank accounts on the myriad failed predictions of Donald Rumsfeld concerning the Iraq War, but the influence such a market would have had on policy debate.

Wolfers and Zitzewitz, 2004 paper, Prediction Markets, outlines the benefits of this concept:

…prediction markets provide three important roles: 1) incentives to seek information; 2) incentives for truthful information revelation; and 3) an algorithm for aggregating diverse opinions. Current research is only starting to disentable the extent to which the remarkable predictive power of markets derives from each of these forces.

Prediction markets provide a preferable alternative to the unethical practice of State Lotteries, which work against the public welfare. State Lotteries bring in public revenues for the state, but rely on a public illiterate in mathematics to purchase lottery tickets. This generates a conflict of interest, as schools, reliant on State Lotteries for funding, are also responsible for educating students to a level of mathematical proficiency to which they would know better than to purchase a lottery ticket.

Prediction Markets, in contrast, not only benefit players with a strong mathematical aptitude, who can understand the probabilities and statistics, but also players who are knowledgable about the subject being wagered. Prediction markets encourage research and promote education among players.

Additionally, prediction markets provide a scientific means of tracking the reliability of our sources. Stanford research psychologist Philip Tetlock surveyed 82,361 predictions by 284 pundits and found them overwhelmingly wrong. Yet the media keep putting these unreliable sources in front of us as if they knew what they were talking about. Imagine how damaging it would be to the reputations of Bill O’Reilly, Keith Olbermann, or other talking head if people were allowed to bet on their predictions and establish a track record for their reliability.

Unfortunately, we cannot currently test this hypothesis, because prediction Markets are gambling and, therefore, illegal. It’s true that players can lose everything in a bad gamble, but the same is true of the stock and housing markets. One person’s gambling is another’s free market. The law should make concessions for well-regulated prediction markets, because they can provide a valuable public service.

Further Reading