Antibiotic Resistance |

This message brought to you by the American Medical Association, Food and Drug Administration, and Centers for Disease Control: There is no scientific evidence that antibacterial soaps and other products have any health benefits, and there is reason to suspect they could contribute to a problem much more dangerous than a bellyache from food poisoning.

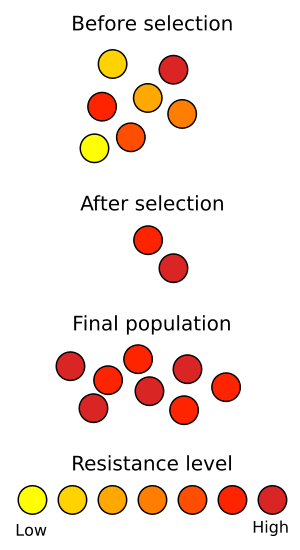

Bacteria are numerous, there are ten times as many microorganisms living in our guts as we have cells in our entire bodies. Bacteria multiply rapidly, doubling in number every 20 minutes under optimal conditions. Bacteria may also transfer genes to one another through plasmid exchanges, providing them the ability to mutate very quickly. All of these characteristics mean they can also evolve very quickly.

Just a few years after penicillin, the first antibiotic, became widely used in the 1940s, penicillin-resistant infections emerged. Today antibiotic resistant bacterial strains have become a global crisis. According to the CDC, 70 percent of the bacterial infections acquired in a hospital each year by 2 million people and resulting in 90,000 deaths are resistant to at least one antibiotic commonly used to treat them. Bacterial strains resistant to multiple antibiotics, also known as “Superbugs,” are beginning to appear in healthy people in communities.

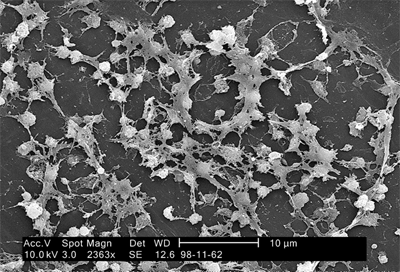

During shoulder surgery at the hospital, my father became infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Doctors prescribed vancomycin, an antibiotic so powerful they had to thread a line through a vein in his arm and into a large vein near the heart where a small dose could be injected over the course of a half-hour, dilluting it into the blood stream so as not to destroy the vein. He was on this prescription, currently the last line of defense in antibiotics, for six weeks. If he had been infected with a vancomycin-resistant Staph aureus, he would be dead now.

Staphylococcus on catheter Credit: CDC |

Antibacterial agents not only appear in soaps, but window cleaners, sponges, Tupperware, mattresses, pillows, sheets, towels, and slippers. If the phenomena of stronger strains of bacteria evolving in hospitals holds true to other environments, then our clean, sterilized homes are becoming breeding grounds for the bacteria responsible for necrotizing pneumonia, severe sepsis and necrotizing fasciitis (“flesh-eating bacteria”).

An FDA panel found that antibacterial soap was no more effective than regular soap at preventing infection. While antibacterial soap kills bacteria, making room for the resistant strains to spread, regular soap simply washes bacteria off the skin and down the drain, leaving the resistant strains in competition with the other bacteria for food and living space.

We can’t win the war on bacteria, we wouldn’t want to. Somewhere between 300 and 1000 different species of bacteria live in our guts, assisting in digestion, training our immune systems, and preventing harmful bacteria from taking up residence in our bodies. An emerging body of research is connecting overly sterile childhood environments to a lack of intestinal microflora in infants and leading to allergies later in life.

Yogurt bacteria, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus, have been shown to improve lactose digestion in people with lactose-intolerance, improve intestinal transit time, and stimulate the gut immune system. These microscopic friendlies are collateral casualties of our antibacterial agents.

And if all these aren’t strong enough arguments, then consider this bumper sticker: “Support Bacteria: It’s the Only Culture Some People Have”

Comments

5 responses to “Antibacterial Soaps are Bad for You”