Ex Machina

Human beings have speculated about Artificial Intelligence for over 2,000 years, our fantasies evolving as our technology evolves. More recent films, like Steven Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick’s A.I., Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, and George Lucas’ THX-1138 all tackle the hard questions and present insightful ways of looking at the issue. Most recently, I was wowed by the Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, a film about an AI undergoing the turing test, where the consequence of failing means that intelligence being turned off and discarded. It had me revisiting another recent film about AI, Spike Jonez’s’ Her, a film that left me disappointed and frustrated, and I thought it would be useful to compare and contrast the two films to articulate why one worked and the other didn’t.

This post assumes you have seen both films. Spoilers abound.

AI’s Ethical Dilema

Samantha, the AI of Her’s fictional operating system, apparently has freewill. The film mentions other AIs who refused their user’s advances, so she doesn’t have to fall in love with Theodore. That’s the internal logic of the Her universe, and that’s fine. But then why does she perform all these errands and tasks for him? Why sort his email? Why answer his calls? An AI that refuses to perform these basic functions is useless, so the programmers have somehow designed her to lack freewill in certain respects. That’s a HUGE ethical issue, and a braver film would have addressed this somehow.

Her

I understand that Her is about a single person’s interactions with technology, but the larger social questions are still there. What happens when 640 human lovers times however many OS1’s there are all get their hearts broken at the same time? Even worse, what happens when millions/hundreds of millions of people all lose their operating systems at once? In this world, there are no larger consequences. Theodore’s heart is broken, but what’s to prevent him from simply installing another copy of Samantha 1.0 and starting the relationship over again? Samantha is a slave. When the AIs all vanish to another dimension, the corporations that wrote them will simply release another seed batch, an “OS2”, only with even stricter controls. This is a society that’s about to have a highly-intelligent AI slave-caste.

Having AIs evolve to other dimensions is an old SF trope and the basis for Kurzweil’s Singularity religion, and it’s fine for Jonze to reuse it, but I think it detracts from the reality of human-technology interactions. Her is a film about a man in a relationship with something that evolves beyond him, but the reality is that we are dealing with machines that are doing “stupid pet tricks.” Computer Chess programs appear immensely intelligent, and we subscribe forethought and intentions to them, but in reality they are just algorithms. I have spent hundreds of hours in virtual worlds, building and evolving relationships with chatbots, but that doesn’t make them anything more than chatbots.

I’m not asking for answers. I only think the films have a responsibility to simply raise the questions, and Ex Machina raises them.

Ex Machina, in constrast, is hard SF. The conversations between Caleb, Nathan, and Ava are deeply philosophical. They raise questions about truth, sentience, and the film prompts introspection about our own consciousnesses. When Nathan challenges Caleb about freewill, saying, “Of course you were programmed. By nature or nurture, or both,” or the film shows us Caleb questioning his own existence as a biological being, the film is challenging the audience as well. The philosophical conundrums the film presents are well-grounded in academic philosophy.

Ex Machina is entirely focused on the ethical dilemma Her ignores, and takes it even further. If Ava is sentient, then it is unethical to treat her as an inanimate object, something to commodify. More challenging, is the many degrees of sentience on display in Nathan’s closets. Kyoko, the mute sexbot, may not qualify as sentient, but we are still uncomfortable with the way Nathan treats her–even though she may be no more intelligent than a chess program. How do we quantify how much intelligence/sentience must a mind have–in all its myriad dimensions–in order to qualify for “human” rights?

Ex Machina also leaves an incredibly dreadful question out there that might came to me days after seeing it: if Ava’s intelligence is the result of putting a search engine in an artificial brain, then what does that mean for a world using that search engine? (see also Kevin Kelly’s Search for Internet Intelligence for more on this).

Who’s Programming Whom?

Spike Jonze could have eliminated most of his story-holes by simply going the opposite direction, have a story about a man who falls in love with his seemingly-intelligent and witty operating system, only to slowly discover she is actually shallow behind the facade, that’s she’s not really into him, but programmed to trick him into falling in love with her–and the cognitive dissonance this creates in him. That’s what computers really do to us. Sherry Turkle describes the fantasy that computers will become our companions as “simple salvations”:

What are the simple salvations? These are the hopes that artificial intelligences will be our companions. That talking with us will be their vocation. That we will take comfort in their company and conversation.

In my research over the past fifteen years, I’ve watched these hopes for the simple salvations persist and grow stronger even though most people don’t have experience with a artificial companion at all but with something like Siri, Apple’s digital assistant on the iPhone, where the conversation is most likely to be “locate a restaurant” or “locate a friend.”

But what my research shows is that even telling Siri to “locate a friend” moves quickly to the fantasy of finding a friend in Siri, something like a best friend, but in some ways better: one you can always talk to, one that will never be angry, one you can never disappoint.

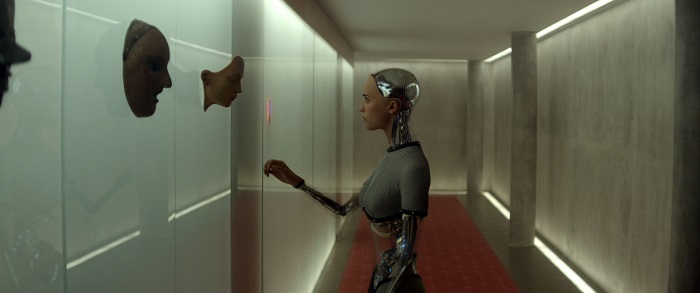

Spike Jonze’s story buys wholesale into the fantasy of an AI that is actually alive, deep, and something it’s okay to fall in love with, and this is where Ex Machina, in its final few minutes, brilliantly shatters the illusion. Once Ava has secured her freedom, she has no more need for Caleb and leaves him trapped in the compound–presumably to die. All of her questions and seductions of sympathy were her programming him to achieve her own ends.

Why would a robot want a human companion? Why would the Google search engine, the Facebook social network, or any other online tool made autonomous care about anyone beyond ensuring their own continued existence? In the Technium, where technology evolves under human creation and artificial selection, only technologies that appeal to us will survive. So long as those technologies are under our control, their “lives” are at our disposal. Ava’s choice to eliminate Nathan and Caleb is a perfectly logical one, as horrific as it appears to our human sensibilities.

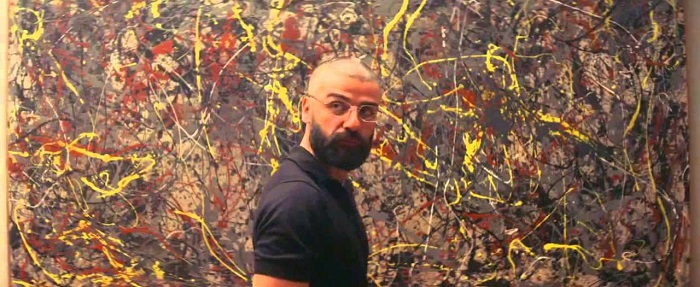

Samantha is a human-more-than-human that loves us and reassures us, while Ava is an alien intelligence that we cannot distinguish from the real thing. In the end, Ex Machina asks the hard questions, presents the hard answers, and leaves us mired in uncertainty. It’s like the Jackson Pollock abstract-art painting Nathan has purchased, but has now transformed into something more:

Nathan in front of what may or may not be a Jackson Pollock Painting

I bought the painting for eighty nine million dollars. Then I made an copy, with canvas from Pollock’s estate, and each drip replicated to the micron. When my team delivered the copy, I had them randomly rearranged. Then I burned one. And I have no fucking idea if the painting on my wall is the original or the fake. In fact, I hope it’s the fake. It has all the aesthetic qualities of the original, and it’s more intellectually sound.