Before becoming a parent, I was well-acquainted with the word “colic.” According to my mother, I suffered from severe colic as a baby, keeping her up all night for weeks with my crying. I’ve also heard parents toss the term about when talking about their baby-raising trials and tribulations. After having our son Sagan, I got to hear the term from one of our pediatricians concerning him having a crying episode one night as a possible explanation for the outburst.

Curious about this seemingly common medical condition, I decided to look up the definition myself:

The strict medical definition of colic is a condition of a healthy baby in which it shows periods of intense, unexplained fussing/crying lasting more than 3 hours a day, more than 3 days a week for more than 3 weeks. [Bold Mine]

There’s that word there, unexplained. For years I thought this word “colic” described a phenomenon that was understood and therefore natural. The etymology of the word, pertaining to “disease characterized by severe abdominal pain” in the early 15th century suggests the infant’s crying is explainable, but in reality the term colic is just a fancy way for your pediatrician to say, “I don’t know why your baby is chronically crying.”

And the more I thought about the word, the more it disturbed me. The phrase “just colic” returns 47,100 google results and is a sentiment I’ve heard more than one parent use. “Just colic” implies that there is nothing to worry about, but not knowing the cause of your baby’s crying is something to worry about. “Just colic” implies that there is little to be done about it, but if you can figure out the cause of the infant’s discomfort then you can do something about it. The word colic is dangerous, because it is ignorance masquerading as knowledge, where the knowledge that your child has acid reflux, the stomach flu, or a food allergy empowers you to do something to treat it and improve your quality of life and your child’s.

The erroneous assumption that because something has a name it also has an explanation is known as the nominal fallacy, and it’s a trap the scientifically-minded fall into all the time that damages our understanding of the world. In his 2011 Edge Question response, Stuart Firestein suggests that recognizing instances of the nominal fallacy in our everyday life would greatly improve our perspective on what we know and don’t know:

Too often in science we operate under the principle that “to name it is to tame it”, or so we think. One of the easiest mistakes, even among working scientists, is to believe that labeling something has somehow or another added to an explanation or understanding of it. Worse than that we use it all the time when we are teaching, leading students to believe that a phenomenon that is named is a phenomenon that is known, and that to know the name is to know the phenomenon.

[…]

In science the one critical issue is to be able to distinguish between what we know and what we don’t know. This is often difficult enough as things that seem known, sometimes become unknown or at least more ambiguous. When is it time to quit doing an experiment because we now know something, when is it time to stop spending money and resources on a particular line of investigation because the facts are known? This line between the known and the unknown is already difficult enough to define, but the nominal fallacy often obscures it needlessly.

“An instance of the nominal fallacy is most easily seen when the meaning or importance of a term or concept shrinks with knowledge,” Firestein explains, using the word “instinct” as an example. The word instinct applies to a living organism’s inclination to a specific behavior in response to a stimulus; in other words, instinct is a label we apply to any animal behavior which we cannot explain as the product of environmental conditioning. Instinct is the nature side of the nature/nurture false dichotomy, and it explains absolutely nothing.

Another example is death by natural causes as it is used in everyday conversation is synonymous with “death by old age,” but there is no such thing in the scientific world. Some failure within the deceased’s body caused the death. If you can explain what happened, it is no longer “natural causes” in the common use of the term; the deceased expired from a specific, nameable cause.

In the medical world death by natural causes is any death by any illness or malfunction of the body; as opposed to, unnatural death which includes accidents and homicides. But this can be extremely misleading as well. When an alcoholic dies of cirrhosis’s of the liver, a lifetime smoker dies of lung cancer, or a family living downwind of a coal power plant dies from pollution exposure, “natural causes” seems inadequate, vague, and outright lazy.

George Gaylord Simpson applied this same logic to a word many people still invoke today as a faux explanation for things we don’t yet understand and who often use it as an excuse to shutdown further inquiry:

Call that great Unknowable by any name you wish, call it X, or Yahweh, or God, or say that God created it. Applying the letters “g”, “o”, and “d” to it or what created it is no explanation and no consolation. It is a common failing, even more among scientists than among laymen, to think that naming a thing explains it, or that we know a thing because we can put a name to it. But to say that God created the universe means nothing whatever.

At the same time, we cannot deny that naming, if used properly, is an important step towards understanding. As Chet Raymo explains:

To name a perceptible thing has some advantage; it makes it possible to talk about it. There can be no theory of the electron, for example, until we have a word for the electron. But naming is not understanding. Before we say we understand a thing, we must weave it into the web of concepts that constitutes a theory. Only when the concept “electron” is enmeshed in a matrix of other ideas — atoms, fields, valency, molecular bonds, etc. — by taut, quantitative connections, do we have confidence that we know what an electron is.

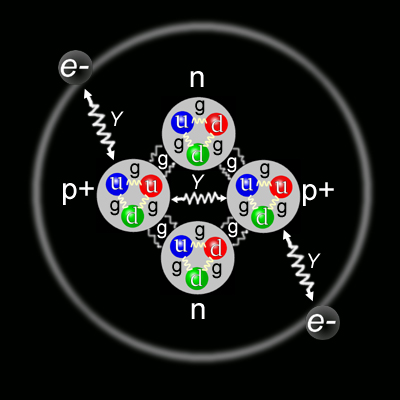

“Electron,” “photon,” “quark,” or other name we give an elementary particle is really just a label for a collection of repeatedly observed characteristics. When we talk about atomic orbitals, we intuitively think of electrons orbiting a nucleus in a manner similar to planets orbiting the sun, like this:

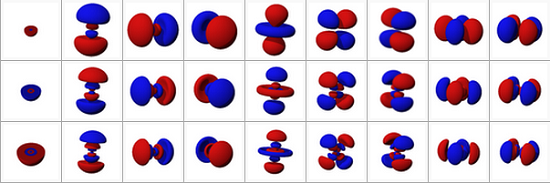

In reality, the “orbit” metaphor only works insofar as to describe the fact that the electron stays in proximity to the atomic nucleus, but beyond that it completely fails. The “orbit” of an electron only defines the area around the atom in which it is most likely to be found, meaning it could be found well outside its orbit at times. I remember how mind-bending it was the first time I saw Wikipedia’s table of orbitals, trying to rationally understand what I was seeing, which the article explains should be thought of as “waves on a circular drum” for some examples and planetary orbits for others:

When we think about the atom and other quantum relics, it’s okay to imagine it in metaphors drawn from our macro-world, so long as we always remember that these are only metaphors, shadows representing a reality completely alien to us. As Niels Bohr best explains it, “We must be clear that when it comes to atoms, language can be used only as in poetry. The poet, too, is not nearly so concerned with describing facts as with creating images and establishing mental connections.”

The wave-particle duality, gravity, dark matter, and dark energy are other examples of phenomena we have named, but for which we do not have truly satisfying explanations. Naming them, acknowledging their existence, was the first step toward understanding through observation and experimentation.

A name for a thing should never mark the end of an inquiry into its nature, but rather a beginning.

Comments

2 responses to “Naming is Not Understanding”