I admit it. I knew better when I posted the story about the kraken lair to my Facebook for my less scientifically literate friends to awe and wonder at. I could tell from the scant evidence provided in the press release that there really wasn’t anything there but a collection of bones from 45-foot-long ichthyosaurs mysteriously piled together at a site in Nevada. To infer the bones were gathered together by a gigantic ancient cephalopod whose soft tissues left no trace in the fossil record was an admirably imaginative idea, but I knew this extraordinary claim didn’t pass the Sagan Standard’s “extraordinary evidence” requirement. As Samuel Clemens best expressed it, “There is something fascinating about science. One gets such wholesale returns of conjecture out of such trifling investment of fact.”

And still I posted it to Facebook, where it got eight Likes, three comments, and one share. That’s eight more Likes than my link to Discovery’s Faces of Our Ancestors gallery, featuring facial reconstructions for 11 ancestors of Homo sapiens and for which there is plenty of direct fossilized evidence to support their stories.

Stories. We only have a few millennias’ worth of stories from the written and oral history of the human race, but the archeological record is brimming with billions of years’ worth of them. Like detectives at the scene of a crime, archeologists have reconstructed events out of the shared story of our origins to tell engaging tales of our ancestors trials and tribulations.

There are tragedies, like the 3-year-old Taung child, whose skull bares the scars of an eagle attack. The Australopithecus africanus child was carried away by a bird of prey 2.8 million years ago. We sense the tragic nature of the story when we consider the horror his parents must have experienced, and at the same time there is the fantastic element of our ancient ancestors having to guard their infants against birds of prey.

I’ve listened to New Age believers explain the giant statues of Easter Island as being erected with the help of aliens, who took the island’s inhabitants away with them into the Milky Way, but there is an important lesson in what we know really happened to this treeless island in the Southeastern Pacific ocean. Jared Diamond reconstructs the history Easter Island with the help of painstaking research by paleontologists and archaeologists, telling the tale of a materialist war, where competing inhabitants chopped down all the island’s trees for transportation and scaffolding so they could erect monolithic statues of increasing size to demonstrate their wealth and prestige. After the trees vanished, so did the large game, and the trash sites on the island show the inhabitants resorted to eating rats and eventually human corpses to survive. The Easter Islanders didn’t have magical powers for levitating boulders, they were an ancient mirror of our modern materialism. The archaeology of Easter Island tells the story of a civilization that fell prey to conspicuous consumption and provides a cautionary tale for a modern society that would sacrifice environmental sustainability for short-term greed.

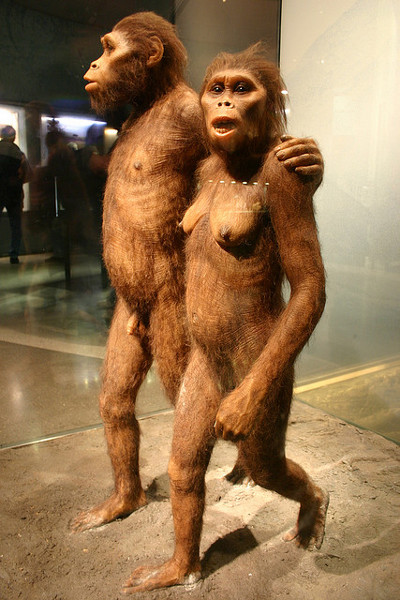

Then there’s the 3.6 million-year-old Laetoli footprints of Austrolopithecus preserved in volcanic ash, large and small, male and female, close together as if they were huddling–perhaps the male had his arm around his mate, and the female’s footprints lopsided as if she were carrying an infant. Imagine what it was like for them, walking fearfully across an ash-covered landscape, a distant bellowing volcano preparing to rain even more ash on them. This story of fear and wonder is reconstructed in this famous diorama:

There are also the mysteries. Homo erectus, who spread halfway across the world before mysteriously vanishing. Imagining her environment, we know there were a greater number of large fauna back then, as humans would come along much later to drive the big animals and predators into extinction wherever they migrated across the Earth. She had stone tools, hand axes she used to chop up game, but was primitive enough and intelligent enough that I read one naturalist refer to her as the “velociraptor of our human ancestors,” which is why I love this statue of her at the Smithsonian Hall of Human Origins lugging a rotting ibex carcass across the Serengeti on her back:

She was a total badass… and then she was extinct.

Where did she go?

As many stories as humans have written in our few millennia of civilization, imagine the number of stories still waiting to be discovered in 3.5 billion years’ worth of geological strata. Stories of tragedy, wonder, mystery, and profundity are all around us, written into the natural world, just waiting for us to read them.

This post has been submitted for the NESCent Blog Contest for Evolution-Themed posts.