Steven Johnson’s Emergence |

The wave phenomenon that occurs at sports stadiums gives the illusion of movement, a rolling surge of activity that sweeps round and round the bleachers. The phenomenon is not confined to any one sport or even any one culture, but occurs around the world in a wide variety of venues.

There is no hierarchy to the wave. No one choreographs its behavior. In reality, we are only seeing individual people acting on a simple rule: If the person to your left stands up, stand up. If the person to your right stands up, sit down. Thousands of individual units following this simple rule generate a spectacular result.

It bares similarity to electrical impulses traveling through heart tissue or the propagation of forest fires. Similar to these phenomenons it merely takes a small cluster of individual instances to instigate it. Just as a spark can create a forest fire, a small cluster of fans can jumpstart a wave. Once begun, it takes on a life of its own.

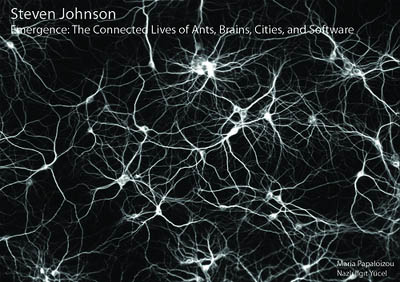

This is one example of how low-level phenomenons create high-level results, a process known as Emergence. In his book of the same name, Steven Johnson explores this phenomenon in growing levels of complexity from slime molds, to ant colonies, to cities, and software.

Understanding how low-level rules can produce high-level organization destroys many “common sense” paradigms. “The Myth of the Ant Queen,” is one such concept Johnson disproves. The Queen ant does not constitute a centralized control for the hive, but is merely another ant programmed with simple rules. The individual ants themselves are also programmed with simple rules that, in the context of the hive, give the illusion of complex organization, when in fact we are observing another “wave” phenomenon.

What about cities then? The majority of the world now lives in cities. They produce the majority of the human race’s culture and innovations. Their inhabitants experience lower infant mortality rates and longer life spans. The cities and ant hives comparison is a commonly recognized pattern among human beings.

Some cities, like Baghdad in Iraq, have existed for thousands of years, perpetually changing and evolving. Like ant hives, cities are multi-bodied organisms. Like cells in a living body, the individual units live within them, unaware of the body’s history and condition. Cities are unregulated, despite what their governing body may argue. They are uncontrolled and their beauty and structure are the result of emergence, built on the actions of the millions of individuals living within them. From slime molds, to ant colonies, to cities, and beyond the book explores the implications of Emergence Theory in a variety of situations.

Johnson convincingly takes Emergence Theory into Futurist speculation concerning software. As computer programs grow to levels of complexity exceeding the Programmer’s centralized control, it will eventually become necessary to turn to a guided Emergence Process to develop them. Programming will eventually begin to resemble gardening, where components and functions are evolved out of a primordial soup of code.

Steven Johnson explores all of these dimensions of Emergence Theory, and he does so with eloquence and an engaging writing style that keeps his subject fascinating with possibilities. He is an English major, not a scientist, and this provides him with the aptitude to convey complex concepts with explanations and examples anyone may understand. For readers who appreciate books that change the way they look at the world, “Emergence” is a must read.

Note: I highly recommend checking out Exploring Emergence, which allows “hands on” experimentation with some of the concepts described in this book.