|

The Marvel Comics revolution, led by Stan Lee, was so immensely successful because it moved the focus of superhero stories from the purely fantastic nature of these beings into the characters behind them. Superman, Wonder Woman, and Batman all had alter egos that were difficult for audiences to identify with. They were two-dimensional, cardboard props until they dawned their costumes and became someone.

Peter Parker, aka. Spiderman, on the other hand, was an everyday kid, dealing with homework, working his way through school, ostracized by his peers, and fumbling through an occasional love interest. Bruce Banner, the Hulk, was a man grappling with a curse that brought potential disaster every time he lost his temper. The X-Men portrayed a flip-side to the superhero icon. Instead of being revered and praised, they were feared and persecuted for their otherness despite their heroic deeds.

Kurt Busiek is an author who revels in characters. In 1994 he collaborated with Alex Ross to write the graphic novel “Marvels.” Now considered a classic, it followed the entire history of the Marvel Comic Universe through the eyes of a reporter, taking photos and relaying his reactions to many of the more famous events in Marvel comic’s history.

The story was something new, another angle on stories we were already familiar with. Instead of running with the superheroes on their adventures, we stood on the ground and watched their battles way up above. We experienced the uncertainty, the fear, the helplessness of being an ordinary citizen in such a world.

The story’s medium was also something new. Busiek and Ross used oil-paintings and live models to convey their story. The result is characters whose faces tell us everything about their personalities in one frame. It was an effect similar to a Rockefeller painting. Here were characters we had seen for decades in simple, cartoonish drawings, and now they were detailed, they were real people.

The problem with “Marvels” was that only readers well-versed in the Marvel legends and lore could truly appreciate it. It was like reading one long series of inside-jokes. It did little to reach out to new readership, but served as more of a fanboy story, preaching to the quior. It was simultaneously fantastic and a waste of talent.

|

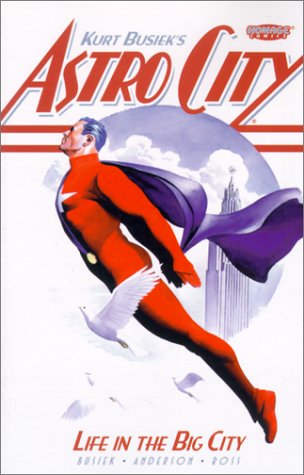

Understanding this history of the shortcomings of comic book stories is important to understanding why Busiek’s later work, “Astro City” was such an accomplishment. Here were characters, built around traditional superhero stereotypes so they could break their moulds. Here was an entire universe from scratch, filled with all the classics, but with new twists.

Take the story of Samaritan, a “Superman” style hero, who we follow around for a day to see what his life is like in the issue “In Dreams.” He dreams of flying, free, like a bird, just for the enjoyment of it, but then his superhero alarm goes off and he must save the world again and again, flying to and fro across the globe in split-seconds. At the end of the day, he tallies how much flying time he was able to get in…

Then there is the Junkman, from the issue “Show ‘Em All,” a burglar so skilled he’s robbed the safe and is long gone before the superheroes can arrive. The problem is that he was so good that he received no recognition, while the superheroes take all the fame. So he goes for another burglary, this time he slips-up on purpose, when the heroes arrive…

Or how about the novelty of getting to play a fly on the wall as we follow the two biggest male and female names in super-heroism as they go out on their first date?

There are epic battles taking place throughout the series; however, they take place in the background of the dramatic situations. Busiek recognized that the audience reads a comic book and since the best narration takes place in the illustrations, this leaves dialogue as the focus. The characters speak for themselves and their facial expression convey the rest.

The comic is the segway between books and video. Kurt Busiek, in “Astro City,” know best how to maximize this medium.

|

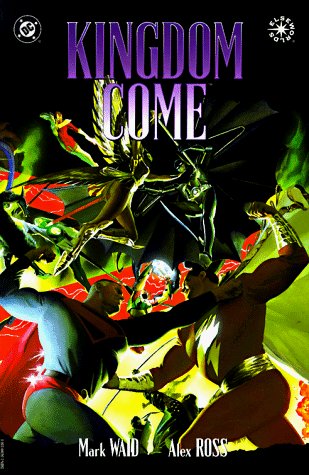

Note: After working with Busiek, Alex Ross went on to do the dramatic “Kingdom Come,” DC Comic’s answer to “Marvels.” It told the story of the superheroes from DC in their later years, after being replaced with the new superheroes of Generation X. It’s also an excellent tale, which explores the conflicting values between generations, but also suffers from the same “inside-joke” issue that was detrimental to “Marvels.”