The 1700s were a century of phenomenal progress in the subject of electricity. Luigi Galvani discovered that electricity made dead muscles twitch, inspiring Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein. Alessandro Volta discovered that electricity was dynamic, flowing through conductive materials like water in a stream, which is why we call it an “electric current.” William Nicholson and Anthony Carlisle discovered that running an electric current through water broke the molecular bonds, generating hydrogen and oxygen, linking the stuff of electricity to the very atoms themselves (Asimov, 1985).

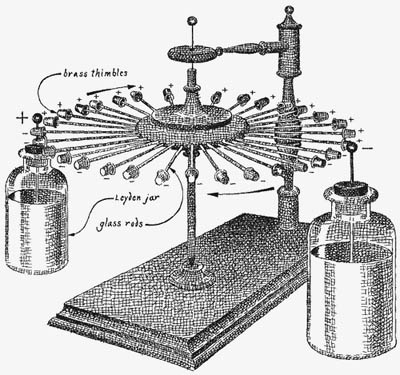

Benjamin Franklin’s electrostatic motor Credit: Peter Collinson, Royal Society |

The great American polymath, Benjamin Franklin, made some major contributions to our understanding of the stuff as well. In his Memoirs there is a section Wonderful effect of points.–Positive and negative Electricity, where he hypothesizes, correctly, that electricity is only one fluid, and electric currents, like static electric shocks and lightning, are the result of an excess of this fluid in one place and a deficit in another, which sought equilibrium.

A, who stands on wax, and rubs the tube, collects the electrical fire from himself into the glass… B, passing his knuckle along near the tube, receives the fire which was collected by the glass from A… To C, standing on the floor, both appear to be electrisied… If A and B approach to touch each other, the spark is stronger, because the difference between them is greater; after such touch there is no spark between either of them and C, because the electrical fire in all is reduced to the original equality… Hence have arisen some new terms among us; we say B is electrisied positively; A, negatively. Or rather, B is electrisied plus; A, minus.

We know now that this “electrical fire” Franklin speaks of is a surplus of electrons, and he was correct that static electric shocks were the result of deficits and surpluses of electrons. The problem was that he had no way of knowing where the surplus, the plus/positive, was. So he took a 50/50 guess… and got it wrong. He meant to give electrons the positive/plus/excess charge, and where they flow to the negative/minus/deficit charge.

For most conceptual purposes, this causes no problems with understanding electricity; however, in thinking of electricity as a flowing entity, it does vex slightly. As Isaac Asimov observes, when recounting how the scientist Michael Faraday used it in naming the two poles between a flowing electric current:

The two poles were “electrodes,” from Greek words meaning “electrical route.” The positive pole was the “anode” (“upper route”) and the negative pole, the “cathode” (“lower route”). This visualized the electric current flowing, as water would, from the higher positions of the anode to the lower position of the cathode.

Actually, now that we follow the electron flow, the electric current is moving from the cathode to the anode, so that, if we go by the names, it is moving uphill. Fortunately, no one pays any attention whatever to the Greek meaning of the words, and scientists use these terms without the slightest feeling of incongruity. (Well, Greek scientists might smile.)

So, thanks to Benjamin Franklin, electric currents are an excess of negatively charged electrons flowing to the deficit of electrons, where there is a positive charge. Thanks to this labeling, we inadvertently labeled the point from which the electrons flow lower and the point to which they flow higher.

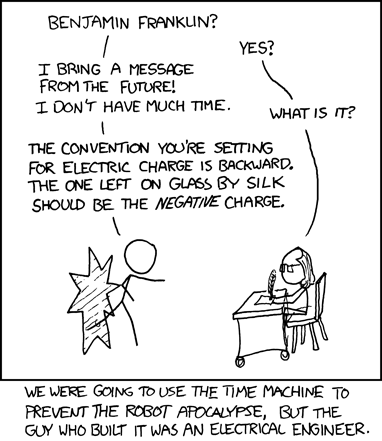

You now have enough background to get the following cartoon:

Urgent Mission Credit: XKCD |

I do have to side with those academics who argue Franklin wasn’t wrong in assigning electrons the negative charge. Electrons and protons could just have easily had their respective charges named “up” and “down,” as we do with some quarks, or “black” and “white,” or “male” and “female.” The labels “positive” and “negative” assign no characteristics to the particles except to describe them as opposites.

Okay… maybe it does irk me slightly. But, living in America, solving this problem has to take a lower priority than adopting the metric system or establishing phonetic spelling.

References

Asimov, Isaac (1985). Salt and Battery, printed in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Mercury Press Inc.

Comments

One response to “Benjamin Franklin’s Electrical Goof”