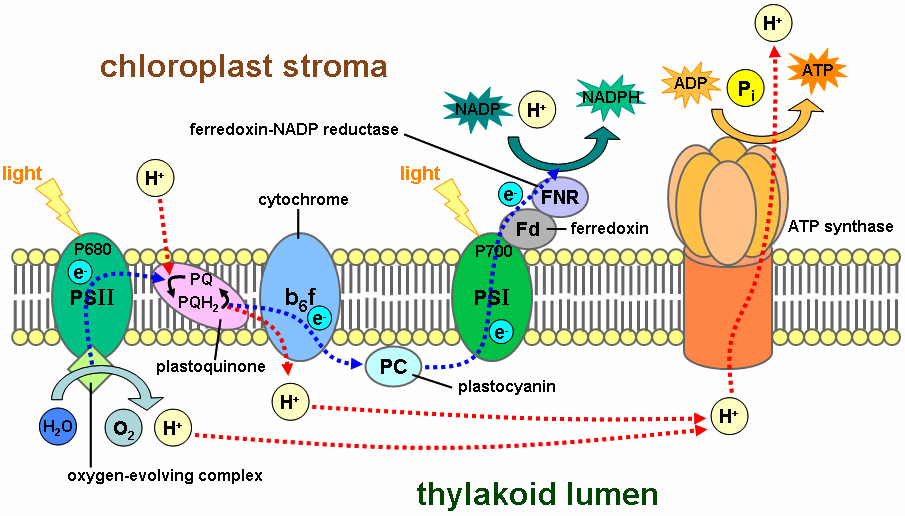

Photosynthetic Electron Transport Chain (Powered by the Sun) Credit: Tameeria at the wikipedia |

So the recent news of researchers synthesizing RNA that can replicate indefinitely kind of stuck with me, particularly the word indefinitely. This isn’t perpetual motion, because the molecule only works so long as it has a supply of molecules to manipulate.

But what if you had a molecule, probably a protein, that interacted with molecules of the same type, bending to modify the structure of the other molecule, and then springing back into its original shape. The next molecule in the chain manipulates the next, and so on, until the chain loops back to the original molecule and the process starts all over again. Wouldn’t that be perpetual motion, this molecular machine running off an infinite transfer of a single electron?

In fact, couldn’t we harness the power of atoms themselves, their random movements, perpetually? Dr. Richard Feynman conceived a device precisely to harness and put this energy to work with his Brownian ratchet:

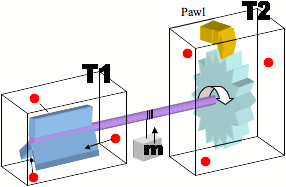

|

Feynman’s Brownian Ratchet |

It’s important to remember that this device is built on a nano-scale. A proper drawing would render it as a molecular construct. The red dots represent hydrogen atoms, actual-size. These are bouncing all over the place through Brownian Motion. All atoms vibrate, even those sequestered in crystals.

T1 represents an itsy-bitsy turbine. As the hydrogen gas atoms bounce into it, they transfer their kinetic energy into it, turning it and the axle leading to T2. The molecular prawl on the molecular gear in T2 makes it so the gear can only turn one way.

With this set up, the turbine will slowly turn around in one direction as the hydrogen atoms bump into its blades, producing work that can be used to wind the string around the axel and lift “m”.

Perpetual Motion, right?

We know it can’t be, despite the fact that someone has tried to patent the idea, so the question becomes, Why not?

Because the ratchet is small enough to be subject to brownian motion itself. In order for it to be small enough to work, it also has to be small enough to shake in such a way that the prawl will slip, allowing the turbine to spin both ways.

One way to overcome the brownian motion is to cool the mechanism to the point where the atoms are no longer vibrating as strongly. In this case, the hydrogen atoms would be warmer, in order to keep them bouncing around, and, as a result, each time a hydrogen atom hit the turbine, it would also transfer some of its heat energy, until the whole system was in equilibrium and work would stop being produced.

Once again, the Second Law of Thermodynamics wins the game.

Comments

One response to “Molecular Perpetual Motion?”