|

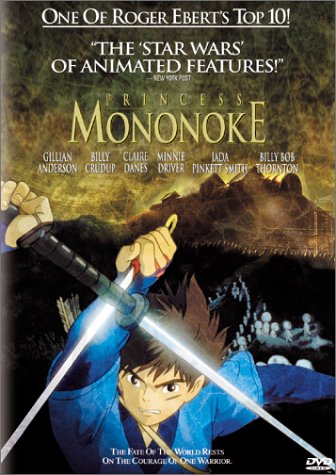

Ashitaka, Prince of the Amishi, a small, peacefull village, has detected a demon approaching. The plant life withers under its touch. Ashitaka pleads with the monster, attempting to calm it and turn it away. When that fails, he kills it as a last resort. During the conflict, he is struck and infected with the God’s poison, fury, and it will kill him. Now banished from his village, he must travel to the land in the West and see what he may see with “eyes unclouded by hate.”

The film takes place at the very beginning of the Iron Age, a transformative time, when the natural world is succumbing to the will of humanity. The conflict surrounds this clash of ages, the industrial and the age of myth and magic. Ashitaka travels through a mystical forest, home of the Forest Spirit, where animals can speak. Encroaching on this world is Iron Town, stripping the mountainsides of vegetation to mine the ores. The Wolf and Boar communities are waging warfare against Iron Town’s citizens, attempting to disrupt their production.

At first glance, it appears industry is the villain, but Ashitaka finds great works of charity and empowering the weak within the town’s borders. While Samurais raid and victimize agriculture-based villages, the guns produced in Iron Town are equalizers. A woman equipped with one is just as deadly as an armored warrior on horseback. The town is even managed by a woman, Lady Eboshi, who hires lepers and the women from brothels, raising them to higher statuses through technology. Our hearts are pulled in different directions as we sympathize with both sides of the conflict.

Ashitaka tries to serve as a diplomat, observing and understanding each side’s perspective, all the while, the rage infecting him struggles to escape. With the Wolfclan, he meets San Mononoke (“spirits of things”), a human girl raised by wolves. They are her family and she identifies with their cause, but she is confused by Ashitaka, his selflessness, a quality she does not associate with the humans.

The setting is pastoral, fantastic, as are all of Myazaki’s works. To watch the film and realize that it takes place without the aid of computer animation is stunning. The film alone is stunning, its magnitude, its majesty.

The world’s of Miyazaki’s films are very Shinto in nature, and this is no exception. From the Boar and Wolf gods, to the Spirit of the Forest, and even the Tree Spirits, we find a world brimming with supernatural forces.

The laws of magic in this ancient world are fuzzy and difficult to comprehend. Is it the bullets or the rage they inspire that transforms the gods into demons? What is the nature of the Forest Spirit? It controls both life and death, but what is the extent of its domain? Even the gods are baffled by its actions, why it saves one life, but ends another.

As viewers, we can only speculate. The ambiguity of the spiritual realm in relation to the physical is a mystery that all religions wrestle with. Perhaps it is like the attitudes of the Forest Animals and the Citizens of Iron Town, incomprehensible because we are only seeing our immediate surroundings and needs in it.

Through all of this stands Ashitaka, the most notable, and refreshing aspect of Myazaki’s storytelling: the altruistic honorability of his protagonists. They succeed because they do not serve their own needs, but the needs of others. Ashitaka runs around all over the place, struggling to prevent violence, and find some form of resolution.

At the film’s end, ask yourself who is left standing, and why.

See Also: Spirited Away, Kee Kee’s Delivery Service, Laputa, Millenium Actress