Jump to:

The Science Fiction of Meditation

Mindfulness Meditation

Science of Mindfulness Meditation

Experimentally-Observed Benefits of Mindfulness Meditation

How to Meditate

References

The Science Fiction of Meditation

Star Wars: The Phantom Menace was a deeply flawed movie on many levels, but there was one moment in the film that I thought was brilliant. The Jedi master Qui-Gon Jinn is in the heat of a duel with the Sith lord Darth Maul, when a force field comes in between them, momentarily pausing their battle. Darth Maul impatiently paces back and forth along the shield, staring at his opponent with murderous rage. Qui-Gon, in contrast, drops to his knees and begins meditating.

Qui-Gon Jinn Meditating

Credit: 20th Century Fox / Lucasfilm

I recently spent a Saturday morning at a meditation workshop hosted by Amma Sri Karunamayi, where I followed a warm-up yoga session taught by my brother (yes, the same one from this epic debate of religion vs science), who was also her devote, with three straight hours of mindfulness meditation interrupted every half hour with my need to change sitting positions in order to restore feeling to my legs. As a skeptic, I had to resist the urge to roll my eyes when they spoke of magical energies stirred by the yogic practice, feeding jade idols butter, and sitting in the presence of a woman who is supposedly the latest incarnation of some Hindu goddess, but also as a skeptic I am open to new experiences and practicing mindfulness meditation for three hours in a group setting where social pressures would help keep me focused was something I strongly desired to try, and I confess I came out of the experience fairly high. I felt like I was floating, calmly detached from the world around me. The feeling carried me through an hour of beltway traffic and I remained non-stressed for the rest of the day.

It was a high very similar to one I would get as a youth from immersing myself in a good book or going deep on a programming task for several hours. Not surprisingly, I was also discovering Star Trek at that time in my life, and was idolizing Mr. Spock for his emotional detachment the cool logic I hoped would help me survive middle school and admired later in life for the idealization of mental discipline. Vulcans are often portrayed in a state of meditation, and Trekkers describe three types of Vulcan meditation:

Mental meditations have the purpose of developing the intellect. One might consider doing a logic puzzle or studying a foreign language a mental meditation, albeit a simple one. Emotional meditations explore the breadth and flavor of our emotions: for one cannot hope to control a thing without first understanding it. Physical meditations consist of various strenuous exercises done in a particularly mindful manner.

I do like the idea of mental and physical meditations, and do practice such disciplines in real life, but the definition here of “emotional meditations” is highly lacking. It doesn’t make sense that one would “explore the breadth and flavor” of something one wants mastery over, but is it possible to cognitively master one’s emotional states and calm the mind of all its chatter?

Mindfulness Meditation

The scientific mind can “entertain a thought without accepting it,” to quote Aristotle. So I can consider meditation, a practice that “has been employed as spiritual and healing practice for more than 5,000 years” objectively based on what scientific scrutiny is out there (Chiesa, 2011). Just because something has been around five millennia, doesn’t mean it’s not nonsense, and just because something finds its origins in religion doesn’t mean it is nonsense.

The word “meditation” invokes mental images of Buddhist monks, drums, gongs, and mountaintops. In fact, the Dalai Lama has done much to promote this stereotype by submitting monks to scientific scrutiny as they meditate. However, as a skeptic, if there are cognitive benefits to meditation, then I want just the secular essence of the practice, trimming away as much ritual and philosophy as possible. For this reason, science is primarily interested in mindfulness meditation as defined by psychologists, which is properly defined, not by the spiritual dimensions of its religious origins, but the observable measurable cognitive and behavioral changes it produces in the practitioner:

Across religions and practices, it is generally believed that meditation leads to a minimization of or reduction of thinking and conceptual activity that allows the practitioner to experience the world without cognitive bias, filters, or models built up from past experience. For example, after meditation, the practitioner should be able to approach a typically stressful situation, such as getting stuck in traffic, with a new perspective or response, such as realizing that being stuck gives him or her extra time to talk with his or her child in the backseat. The idea is that the automatic and typical reaction, such as swearing and brooding about disdain for the driver coming up the breakdown lane, now becomes a choice as opposed to an inevitability (Wenk-Sormaz, 2005).

So mindfulness meditation (MM) should help us overcome our “cognitive bias, filters, or models built up from past experience.” In Zen Buddhism, this is known as the concept of Shoshin or “Beginners Mind”:

Rather than observing experience through the filter of our beliefs, assumptions, expectations, and desires, mindfulness involves a direct observation of various objects as if for the first time …mindfulness practice should facilitate the identification of objects in unexpected contexts because one would not bring preconceived beliefs about what should or should not be present (Bishop, 2004).

By eliminating preconceptions, MM should open the mind to see things to which our experiential biases would normally blind us. In much of the literature studying MM the concept of “automation,” our kneejerk reactions to stimuli and tasks we perform without thinking, is studied:

Both Deikman and proponents of early models of automaticity described automatization as the process that occurs with the repetition of an action or behavior wherein the intermediate steps of the behavior disappear from consciousness awareness.

This is also known as the Enstellung effect or the “creation of a mechanized state of mind,” demonstrated with Luchins’and Luchins’ Water Jar Experiment where subjects got into the habit of using the same algorithm to solve all problems, when some problems could be solved with simpler more efficient steps. I personally fall into this trap all the time working on the computer, copying-and-pasting things manually for an hour when I could write a simple script or use a spreadsheet formula to streamline a task or neglecting keyboard shortcuts for the habit of using the much more inefficient mouse to navigate the user interface.

Although it was not listed in the peer-reviewed articles I read, another reason for pursuing Mindfulness Meditation could be to practice seeing the world in a clearer light, without the perceptual illusion of existence distinctive from the world around us. Susan Blackmore, in her book The Meme Machine, describes something very akin to Mindfulness Meditation as a means of overcoming the selfplex, the illusion that there is a conscious self inside our heads distinct from the physical world:

If my understanding of human nature is that there is no conscious self inside then I must live that way–otherwise this is a vain and lifeless theory of human nature. But how can ‘I’ live as though I do not exist, and who would be choosing to do so?

One trick is to concentrate on the present moment–all the time–letting go of any thoughts that come up. This kind of ‘meme-weeding’ requires a great concentration but is most interesting in its effect. If you can concentrate for a few minutes at a time, you will begin to see that in any moment there is no observing self. Suppose you sit and look out of the window. Ideas will come up but these are all past- and future-oriented; so let them go, come back to the present. Just notice what is happening. The mind leaps to label objects with words, but these words take time and are not really in the present. So let them go too. With a lot of practice the world looks different; the idea of a series of events gives way to nothing but change, and the idea of a self who is viewing the scene seems to fall away.

Another way is to pay attention to everything equally. This is an odd practice because things begin to lose their ‘thingness’ and become just changes. Also, it throws up the question of who is paying attention (Blackmore 1995). What becomes obvious, in doing this task, is that attention is always being manipulated by things outside yourself rather than controlled by you. The longer you can sit still and attend to everything, the more obvious it becomes that attention is dragged away by sounds, movements, and most of all thoughts that seem to come from nowhere. These are the memes fighting ti out to grab the information-processing resources of the brain they might use for their propagation. Things that worry you, opinions that you hold, things you want to say to someone, or wish you hadn’t–these all come and grab the attention to everything disarms them and makes it obvious that you never did control the attention; it controlled–and created–you.

These kinds of practices begin to wear away at the false self. In the present moment, attending equally to everything, there is no distinction between myself and the things happening. It is only when ‘I’ want something, respond to something, believe something decide to do something, that ‘I’ suddenly appear. This can be seen directly through experience with enough practice at just being.

This insight is perfectly compatible with memetics. In most people the selfplex is constantly being reinforced. Everything that happens is referred to the self, sensations are referred to the observing self, shifts of attention are attributed to the self, decisions are described as being made by the self, and so on. All this reconfirms and sustains the selfplex, and the result is a quality of consciousness dominated by the sense of ‘I’ in the middle–me in charge, me responsible, me suffering. The effect of one-pointed concentration is to stop the processes that feed the selfplex. Learning to pay attention to everything equally stops self-related memes from grabbing the attention; learning to be fully in the present moment stops speculation about the past and future of the mythical ‘I’. These are tricks that help a human person (body, brain and memes) to drop the false ideas of the selfplex. The quality of consciousness then changes to become open, and spacious, and free of self. The effect is like waking up from a state of confusion–or waking from the meme dream.

Similar to Blackmore’s above concept of losing the “I” illusion is the concept of “decentering” in psychological circles:

A shift in one’s cognitive perspective known as decentering or disidentification is thought to lead to a change in one’s relationship to negative thoughts and feelings such that one can see negative thoughts and feelings simply as passing events in the mind rather than reflections of reality (Lau, 2006).

Professor J. H. Flavell observed that children do not think about thinking, and coined the term metacognition to describe the phenomena of adults being able to pause and evaluate why we feel certain ways. This “cognition about cognition” is an important piece of an adult’s emotional maturity. “Cognitive strategies are invoked to make cognitive progress,” Flavell writes, “metacognitive strategies to monitor it (Flavell, 1979).”

So mindfulness meditation is a kind of metacognition, but also the practice of eliminating cognition. It is the practice of not thinking, but when a thought arises, as our brains have evolved to do, we observe it and let it go. This practice of becoming a blank slate is hypothesized to alleviate our biases, restore our plasticity of mind, allow us to perceive the world more clearly, and improve our emotional well-being.

Science of Mindfulness Meditation

When we look at the iconic photo of Thich Quang Duc’s self-immolation, we cannot help but feel his decades of meditative practice gave him the strength to so stoically endure such a gruesome death.

Journalist Malcolm Browne’s photograph of Thich Quang Duc during his self-immolation.

Credit: wikipedia

How do scientists quantify the emotional and cognitive benefits of meditative practices that are taking place entirely inside the practitioner’s head? When people work out, scientists can observe the growth in their muscles and performance at physical tasks after observing their nutritional intake and workout practices. When people study, scientists can subject them to intelligence and subject matter tests throughout the process to see how effectively they are learning based on source materials and study habits.

Studies on meditation tend fall into two categories: the effects of short-term Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) courses on the abilities of individuals to perform various tests and the effects of long-term disciplined meditative practice on the physiological structure of the brain.

A justifiable skepticism in the scientific community concerning MM studies because meditation has its origins in religion and is therefore subject to selection bias. Studies must eliminate the religion bias by using secular meditation and random subjects (Wenk-Sormaz, 2005). An additional problem with studies involving long-term meditators is that results are only corollary, as we don’t know if meditative practice results in improved cognition or if individuals with better cognitive skills are drawn to meditative practice. The problem with short-term subjects taking part in a weekend retreat is that we don’t get to measure the long-term effects of MM; additionally, since most studies are performed by psychology college professors, they are also subject to the selection bias of using college students, the “white rat” of human experimentation (Smart, 1966). None of the studies I read on this subject seemed to really get away from these biases, so their findings need to be considered in that light.

Another issue in studying the effects of mindfulness meditation is establishing a consensus definition of what it means to practice it. MM is Incorporated into Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), each with their own slightly different take on it. So what is the essence of MM? Here’s one summary of the literature:

The first component of mindfulness is usually referred to as a mental state characterized by full attention to internal and external experiences as they occur in the present moment. The second component is usually described as a particular attitude characterized by non-judgment of, and openness to, current experience, which is supposed to lead to higher levels of exposure to negative stimuli and emotions as well as to higher acceptance and concurrent reduction of experiential avoidance (Cheisa, 2010).

There is also the issue of quantification. What are we to measure in the MM practitioner? Meditation must result in a distinctive and reproducible state with reportable phenomena, the state must develop specific traits, there must be measurable progress in the practices (Lutz, 2007). Here is a survey of different results various studies have attempted to measure in subjects:

A number of processes have been proposed to underlie training in mindfulness. The most commonly cited of these is relaxation (Dunn, Hartigan, & Mikulas, 1999), although it has been suggested that this is at most a beneficial side effect of mindfulness practice, rather than an inherent process (Baer, 2003). Another hypothesized process is a reduction in over-general autobiographical memory (Williams, Teasdale, Segal, & Soulsby, 2000). There may also be an erosion of the use of literal, evaluative language (Hayes, 2003; Hayes & Shenk, 2004). Acknowledging rather than evaluating thought processes circumvents the usual cognitive defenses which attempt to prolong or avoid such processes. This results in an increased range and flexibility of actions (Hayes, 2003) and has been termed cognitive flexibility (Roemer & Orsillo, 2003). Mindfulness training may also facilitate metacognitive insight (Bishop et al., 2004; Mason & Hargreaves, 2001; Teasdale, 1999; Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 1995). This represents a transition toward viewing thoughts as ephemeral mental events, rather than as direct representations of reality. Such “decentering” somewhat distances us from our problematic thoughts and emotions, allowing us to address them consciously rather than merely reacting to them (Chambers,2008).

How are these measured? With a wide variety of psychological assessment tools such as the Tellegen Absorption Scale (TAS), Situational Self-Awareness Scale (SSAS), Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ), Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES), NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO_FFI), Psychological Mindedness Scale (PMS), Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ), Marlow-Crowne Social Desirability Scale, Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Scale (KIMS), Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), Mindfulness Questionare (MQ), Revised Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale (CAMS-R), and many others (Where possible, I have attempted to link to actual versions of tests, then wikipedia articles, and finally abstracts on them).

One very common test is the stroop task for measuring deautomization, where participants identify the color of a word that identifies a different color.

Stroop Task

The stroop task is a favorite for measuring deautomation because:

The automatic semantic activation of the word meaning must be overridden in order for participants to respond correctly when faced with incongruent words. As reading is automatic for proficient readers less attentional resources are required for reading irrelevant (neutral) words than for ink colour naming. Consequently, the reading of the word appears obligatory and results in an increase in reaction times and errors when attempting to process incongruent colour words. Increasing the performance in this task would therefore require the reinvestment of attention (deautomatisation) and a non-habitual response (Moore, 2009).

Other tests are intended to measure autobiographical memory, which “works by first recalling a generalized memory, then specific events are recalled from that generalization. If the process is interrupted, then we are left with only the overgeneralized memory (OGM).” Subjects are tested on their ability to recall details of past events, requiring focus, reflection, and emotional stability.

Still others test subjects’ attention. For instance the Change Blindness Flickering Task flashes the same photo twice with one difference between the two instances (ie. the height of a railing behind a couple), or the Gorrilla Video, where the subject is tasked with counting dribbles and passes of basketball players in a video and a person in a gorilla suit walks behind the scene, but 22% of participates don’t notice (Hodgins, 2010).

Experimentally-Observed Benefits of Mindfulness Meditation

Cognitive Flexibility

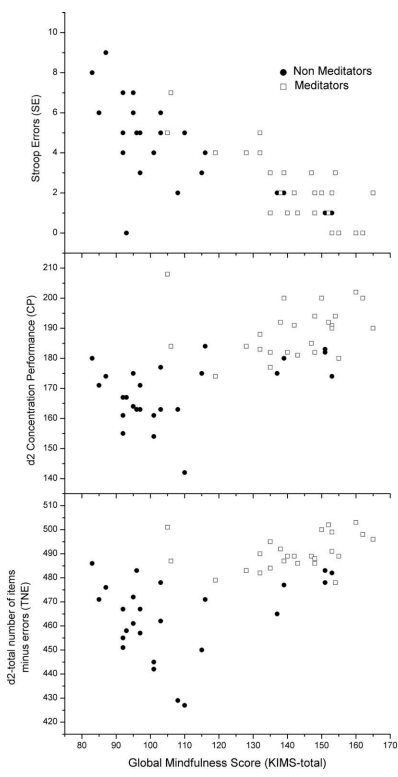

A picture–or in this case a scatter plot graph–paints a thousand words, so check out how meditators do against non-meditators on the stroop and concentration tasks:

These near-linear results explained:

Positive correlations were found with the d2-scores TN (r = .510, p < .001), TN _ E (r = .620, p < .01), CP (r = .667, p < .01) and the Stroop-score TNP (r = .331, p < .05). This indicates that high levels of mindfulness are correlated with high processing speed, good attentional and inhibitory control, and a good coordination of speed with concurrent accurate performance. Negative correlations were found with the d2-errors E (r = +/-.527, p < .001), E1 (r = +/-.493, p < .001), E2 (r = +/-.398, p < .01) and the Stroop error SE (r = +/-.780, p < .001), signifying that higher levels of mindfulness are linked to reduced errors across measures, suggesting greater attentional control, accuracy of visual scanning, inhibitory control, carefulness, cognitive ?exibility and quality of performance. These results support the hypothesis that mindfulness would correlate positively with task performance. (Moore, 2009)

The sample-size for the above study was small however, consisting of 25 Buddhist meditators and 25 non-meditators recruited from a local credit management company. So the study doesn’t isolate the meditative practice from the religious practice, but it is interesting that the Buddhists outperformed “telephone operatives, team leaders, IT technicians, finance workers, account managers, upper management and marketing executives,” as these are professionals whose jobs demand high-levels of concentration.

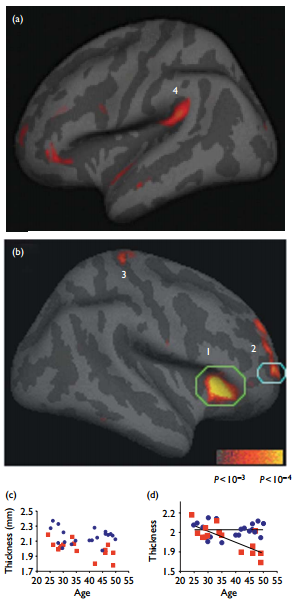

Another small sample size of 20 “Western meditation practitioners” found “meditation is associated with increased thickness in a subset of cortical regions related to somatosensory, auditory, visual and interoceptive processing” in participates who practiced meditation for an average of nine years for six hours a week (Lazar, 2005):

In addition to the small sample size, the authors remind us that “correlation is not causation.” It might be possible that individuals with a pre-existing thickening of these cortical regions are drawn to meditation; however, looking at the scatter plot, it is interesting to see the way the blue-circles (meditators) and red-squares (non-meditators) diverge with age. As we grow older we lose our plasticity of mind, and if this cortical thickening is not pre-existing, then meditative practice would appear to provide another tool in the kit of strategies for staving off this cognitive decline as we grow older.

Another more recent experiment that included a mixture of experienced meditators and individuals interested in learning meditation, some given actual mindfulness training and a control group, found meditators experienced reduced cognitive rigidity in tests:

following repetitive experience with a complex problem solving method, experienced mindfulness meditators were less blinded by experience and were better able than pre-meditators to identify the simple novel solution… similar results were obtained following mindfulness training in which participants were randomly assigned to mindfulness training vs. waiting list groups. These findings lend support to the notion that mindfulness involves cultivation of a “beginner’s mind,” and demonstrate that mindfulness practice reduces cognitive rigidity via the tendency to overlook simple novel solutions to a situation due to rigid and repetitive thought patterns formed through experience (Greenberg, 2012).

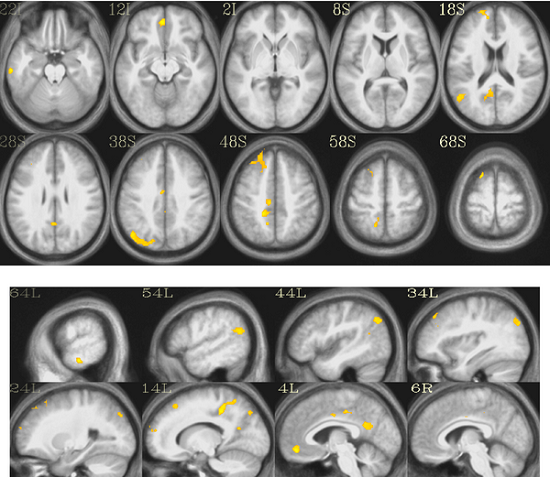

Brain scans of meditators and controls performing tests for automated thinking, distinguishing words from non-words, in another study found experienced meditators had faster reaction times in distinguishing words from non-words in tests where texts were flashed at them at random, suggesting meditative practice improves the brain’s ability to switch tasks by suppressing its tendency to wander into spontaneous thought:

While behavioral performance did not differ between groups, Zen practitioners displayed a reduced duration of the neural response linked to conceptual processing in regions of the default network, suggesting that meditative training may foster the ability to control the automatic cascade of semantic associations triggered by a stimulus and, by extension, to voluntarily regulate the flow of spontaneous mentation. (Pagnoni, 2008)

Memory

Studies have also found meditation to improve memory specificity:

Compared to matched controls, MBCT participants showed increased autobiographical memory specificity, decreased overgenerality, and improved cognitive flexibility capacity and capacity to inhibit cognitive prepotent responses. Mediational analyses indicated that changes in cognitive flexibility partially mediate the impact of MBCT on overgeneral memories. (Heeren, 2009)

My understanding of this science is shallow, but it appears that when we try to remember events from our lives, we are able to locate the general memory quite easily, but if other thoughts get in the way, we aren’t able to go deeper to summon specific details about the event. This might be because feelings get in the way or spontaneous cognition interrupts the process. MBCT may improve autobiographical memory by encouraging:

…patients to practice noticing elements of their experience and to do so in a nonjudgmental way. In this way, it encourages not only more specific encoding of events but also more specific retrieval of past events by reducing the tendency for individuals to abort the search process. Further research will be needed to establish how much of the change in memory comes about as a result of the MBCT’s effect on encoding versus retrieval. (Williams, 2000)

Cognitive Well-Being

Finally, mindfulness meditation is found to promote an overall improved sense of well-being and emotional maturity. One of the most challenging finds came from a study that found meditators were capable of overcoming their sense of personal offense in a situation and accept what was best for themselves. In a study of the Ultimatum Game, where an acquaintance is given $20 and told to share it with you, if you decline what they offer, neither of you get any money. When offered $1, most people will reject the offer to punish the person’s selfishness, even though this isn’t a rational decision. Meditators were much more likely to make the rational decision to accept the offer of $1 (Jones, 2012).

I did not read the research into MBCT being used for treating mental disorders such as depression, but summaries of the research did find positive results in specific cases (Chiesa, 2010). Additionally, more experienced Meditators had more curiosity and a higher level of decentering (Lau, 2006). Mindfulness training reduces maladaptive ruminative thinking and increases adaptive ruminative thinking (Heeren, 2011). Subjects given mindfulness training “demonstrated significant improvements in self-reported mindfulness, depressive symptoms, rumination, and performance measures of working memory and sustained attention, relative to a comparison group who did not undergo any meditation training (Chambers,2008).”

How to Meditate

Meditation is focus, a balance between not letting the mind become bored or falling asleep and not letting the mind become too excited and run away into daydreams. You are cultivating two faculties: “a meta-awareness that recognizes when one’s attention is no longer on the breath, and an ability to redirect the attention without allowing the meta-awareness to become a new source of distraction (Lutz, 2007).” Err on the side of focus starting out, focusing on the present moment and on your breath until you are able to focus on nothing and pursue the goal of thinking nothing at all.

But it is also practicing the meta-awareness of your thoughts:

Although mindfulness, or insight meditation, also includes some concentrative practices, the focus of attention is unrestricted such that the meditator develops an awareness of one’s present experience, including thoughts, feelings, or physical sensations as they consciously occur on a moment-by-moment basis (Lau, 2006).

This is cognitive diffusion “the ability of recognizing thoughts as thoughts and not necessarily as an accurate readout of reality.” It is looking at our thoughts in the third-person, so instead of thinking “I am a bad person,” you observe yourself having the thought “I am having the thought that I’m a bad person (Chiesa, 2011).”

Vulcan Meditation Lamp

Credit: Paramount

Although it sounds easy, meditation is an exercise in self-regulation. It’s very similar to physical exercises in that the longer your session goes, the harder it is to maintain. Just as you reach a point of exhaustion at the gym, where even the lightest weights become too heavy to lift or the slowest pace on the treadmill becomes too difficult to run, there is a point of mental exhaustion during a meditation session. It seems to me that this cognitive weariness is probably related to the fact that we appear to have a limited reservoir of willpower in our brains, but we can strengthen that area of the brain with practice just like anything else.

The goal of meditation is to carry over the state of mind from the act of meditation into the non-meditative daily life (Lutz, 2007). That’s why, like exercise, you have to work it into your daily life and not just when you escape to retreats removed from the world. It’s easy to be mindful and at peace when you don’t have the stress of the everyday world on your shoulders. What’s tough is remaining mindful and relaxed despite work deadlines, traffic jams, slow fast food lines with a grumbling stomach, irritating peers, political attack ads, and the thousand little cuts that push us into ruminative thinking and automated behaviors.

Science Koans

Zen meditation has the practice of “focusing on a koan, a specific riddle that is unsolvable by logic, which is said to lead the practitioner to an insight into the true nature of reality (Chiesa, 2011).” Scientists don’t need riddles like the “sound of one hand clapping” or falling trees making sounds in forests, we have the riddles of reality to meditate on. Here are some “science koans” to deeply consider at the opening of a meditation session to ease you into deeper meta-awareness:

- Erwin Schrodinger: Life Feeds on Negative Entropy, “sucking orderliness from its environment.”

- Carl Sagan: The Cosmos is just right intellectually, where things are knowable, making existence bearable for thinking beings, but complex enough to offer us seemingly endless challenges.

- Lord Kelvin: Atoms are so small that if you poured a glass of water into the ocean and gave them time to distribute evenly, when you later took a glass from the ocean you would find a hundred of the original molecules within it.

- Lewis Fry Richardson: “Big whorls have little whorls / Which feed on their velocity / And little whorls have lesser whorls, / And so on to viscosity.

- Willem de Sitter: We live in a Universe where gravity pulls galaxies towards one another, but universal expansion pulls them apart.

- Jacques Monod: All life is made of lifeless sub-components below the level of the cell.

- Sir John Randall: An egg is a chemical process with the power to become a lifeless omelet or a living chicken.

- Sir James Hopwood Jeans: Everything is vibrations, light and other forms of radiation are roaming vibrations and matter is bottled up vibrations.

- Stephen Hawking: The total energy of the Universe is Zero.

- Arthur Koestler: The Cartesian Duality, the idea that our mind is separate from our matter, is an illusion.

- Banesh Hoffman: Light is both spread out and localized.

- Granville Stanley Hall: Everything society builds and every social interaction we have with others is a plexus of motor habits.

- A. S. Eddington: All matter is mostly empty space.

- A. S. Eddington: The second law of thermodynamics as a profound distinction between past and future.

- George Gaylord Simpson: The origin of the universe is ultimately unknowable.

Meditation for the Scientist/Skeptic

Scientists and intellectuals have a jump on the average person when it comes to meditation. We have spent countless hours deeply immersed in texts, focusing on the single object of the book and preventing the mind from wandering. Similarly, when we work for long hours on a problem, we are highly focused in the moment. The high I get from reading a good book or programming for an extended period of time is similar to the one I get from an hour of meditation. Intellectuals have the attention part down, we simply need to move our attention from a specific thing to no-thing. Chet Raymo describes prayer as silent observation, which is essentially mindfulness meditation. Simply pay attention without judgment, and when we do judge, note it and let it go.

Easier said than done, but that’s why we practice it.

References

Anderson ND, Lau MA, Segal ZV, Bishop SR (2007) Mindfulness-based stress reduction and attentional control. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 14(6): 449–463. 10.1002/cpp.544. (link)

Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, et al. (2004) Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 11(3): 230–241. (link)

Camerer, Colin; George Loewenstein & Mark Weber (1989). “The curse of knowledge in economic settings: An experimental analysis”. Journal of Political Economy 97: 1232–1254.

Chambers R, Lo BCY, Allen NB (2008) The impact of intensive mindfulness training on attentional control, cognitive style, and affect. Cognitive Therapy and Research 32(3): 303–322. 10.1007/s10608-007-9119-0.

Chiesa A, Calati R, Serretti A (2010) Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clin Psychol Rev 31: 449–464.

Chiesa A, Malinowski P (2011) Mindfulness-based approaches: Are they all the same? J Clin Psychol 67(4): 404–424. 10.1002/jclp.20776.

Colin, Loewenstein, Mark, The curse of knowledge in economic settings: An experimental analysis, Journal of Political Economy , 97: 1232–1254

(link)

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and metacognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34, 906–911.

Greenberg J, Reiner K, Meiran N (2012) “Mind the Trap”: Mindfulness Practice Reduces Cognitive Rigidity. PLoS ONE 7(5): e36206. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036206 (link)

Heeren A, Philippot P (2011) Changes in ruminative thinking mediate the clinical benefits of mindfulness: Preliminary findings. Mindfulness 2(1): 8–13. (link)

Heeren A, Van Broeck N, Philippot P (2009) The effects of mindfulness on executive processes and autobiographical memory specificity. Behav Res Ther 47(5): 403–409. (link)

Hinds, Pamela J. (1999).The Curse of Expertise: The Effects of Expertise and Debiasing Methods on Predictions of Novice Performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 1999, Vol. 5, No. 2,205-221 (link)

Hodgins HS, Adair KC (2010) Attentional processes and meditation. Conscious Cogn 19: 878. (link)

Jha, A.P., Krompinger, J., & Baime, M.J. (2007). Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(2), 109–119. (link)

Jones, Sarah Bruyn (2012), An endless exploration, The Roanoke Times. (link)

Lau, M., Bishop, S.R., Segal, Z.V., Buis, T., Anderson, N.D., Carlson, L., Shapiro, S., Carmody, J., Abbey, S., & Devins, G. (2006). The Toronto Mindfulness Scale: Development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(12), 1445–1467.

Lazar, S.W., Kerr, C.E., Wasserman, R.H., Gray, J.R., Greve, D.N., Treadway, M.T., McGarvey, M., Quinn, B.T., Dusek, J.A., Benson, H., Rauch, S.L., Moore, C.I., & Fischl, B. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. NeuroReport, 16, 1893–1897. (link)

Lutz A, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ (2007) Meditation and the neuroscience of consciousness: An introduction. Anonymous The Cambridge handbook of consciousness. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. pp. 499–551.

Moore A, Malinowski P (2009) Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility. Conscious Cogn 18(1): 176–186. (link)

Pagnoni G, Cekic M, Guo Y (2008) “Thinking about Not-Thinking”: Neural Correlates of Conceptual Processing during Zen Meditation. PLoS ONE 3(9): e3083. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003083 (link)

Smart, Reginald G. (Apr 1966) Subject selection bias in psychological research. Canadian Psychologist/Psychologie canadienne, Vol 7a(2), Apr 1966, 115-121. doi: 10.1037/h0083096

Wenk-Sormaz H (2005) Meditation can reduce habitual responding. Adv Mind Body 11: 48–58. (link)

Williams, J.M.G., Teasdale, J.D., Segal, Z.V., & Soulsby, J. (2000). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy reduces overgeneral autobiographical memory in formerly depressed patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(1), 150–155. (link)

Zeidan F, Johnson SK, Diamond BJ, David Z, Goolkasian P (2010) Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Conscious Cogn 19(2): 597–605. (link)

Comments

One response to “The Science of Mindfulness Meditation and Practice for the Rational Skeptic”