Imagine No Religion |

“Religion has actually convinced people that there’s an invisible mand–living in the sky–who watches everything you do, every minute of every day. And the invisible man has a special list of ten things he does not want you to do. And if you do any of these ten things, he has a special place, full of fire and smoke and burning and torture and anguish, where he will send you to live and suffer and burn and choke and scream and cry forever and ever ’til the end of time… But he loves you!

– George Carlin

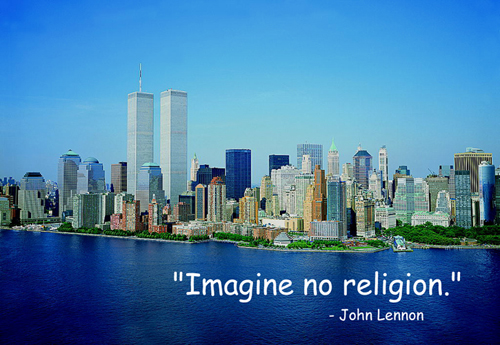

Despite how American politicians try to spin the World Trade Center attacks for their own ends. The 9/11 terrorists were not going to war against American’s “freedom,” they were attacking our secularism. America and other Western countries tend toward pluralism and naturalism. Our governments were founded on a mostly pragmatic and evolving empirical understanding of the world.

When the “jihadists” flew passenger jets into the Twin Towers, they were attacking what the Middle East saw as the icon of the West’s materialism. They were attacking our empiricism, and assaulting a culture not founded on Abrahimic religious laws. They were attacking our disbelief.

Richard Dawkin’s book The God Delusion, does not appear to have much to add to the debate on theism versus atheism, and that is the book’s great strength. Instead, Dawkins draws upon the great world history of atheist thinkers and religious skeptics from icons such as Thomas Jefferson to modern comedians such as Julia Sweeney. By focusing and promoting the ideas of other great skeptics, Dawkins puts the emphasis of his book on the truth of these ideas and their broad support across a diverse collection of educational and historical backgrounds.

Dawkin’s takes critical aim of Stephen J. Gould’s concept of ‘non-overlapping magisteria (NOMA),’ used to draw a strict dichotomy between the realms of science and religion. Gould argued that natural laws were the realm of science, while deriving meaning and purpose to the world were the realm of religion.

As we have seen with the Creationists assault on public school ciriculums, religion has no intention of respecting the borders between the Empirical and Spiritual. As we saw on 9/11, religionists are outraged to the point of commiting spectacular acts of violence against our secular Western civilization. Religion has no intention of honoring NOMA; therefore, it’s the responsibility of secularists to argue Empiricism’s superiority over the unprovable.

Dawkins wonderfully takes apart the modern notion that, without religion, we would have no reason to act morally toward one another. By surveying the litany of atrocities commited god and his chosen prophets in the Old Testament, and Jesus’ lack of family values in the New Testament, Dawkins banishes this illogical argument:

The God of the Old Testament is arguably the most unpleasant character in all fiction: jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving control-freak; a vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser; a misogynistic, homophobic, racist, infanticidal, genocidal, filicidal, pestilential, megalomaniacal, sadomasochistic, capriciously malevolent bully (Dawkins).

We are more moral than the prophets of the Old Testament, which tells the story of Abraham preparing to sacrifice his son, Isaac, for god, when god stays his hand. Today, Abraham would be locked up for child abuse. When criminals claim god compeled them to commit their crimes, we don’t excuse the offense because our law is not Biblical. The Old Testament is so foul, Dawkins observes, that if it were not a sacred text, people would not leave it lying out for children to stumble upon.

While it is true that history holds examples of atheists who were monsters, such as Stalin and, possibly, Hitler. They did not commit their atrocities in the name of atheism. No one has ever blown up a clinic or shot a doctor in the cause of disbelieving in god. Scientists don’t strap bombs to themselves and detonate them in crowded public places because that culture doesn’t accept the theory of evolution. The difference between the existence of good and bad people within atheist circles and those of religious circles, is that the religionists are the ones who use their gods as a justification for their inhumane behaviors.

Dawkins also puts yet another fact on the mountain of arguments crushing creationist ideology, when he refutes their argument that evolution is a random process and that complexity cannot rise from chaos. Natural Selection, Dawkins points out, is not random at all. In fact, it is just the opposite; it is a clearly defined process that naturally brings order out of disorder.

Dawkins most original observation comes when he looks at teaching religion as child abuse. He uses the example of a woman raised in the Catholic church who was sexually abused, but who also found the memory of that abuse nowhere near as scarring as the psychological abuse the church inflicted on her with the threat of Hell and the nightmares of her dead loved ones in spending eternity in torment.

Dawkins also points out the evangelical Hell House, where parents are encouraged to bring children as young as 12 years to see the most horrifying depictions of eternal damnation. The difference between these and a Halloween haunted house is that children are taught that what they are seeing is real and awaits them if they don’t believe in Jesus.

Jill Mytton, a psychologist, runs a support group for survivors of abusive religious upbringings like the ones mentioned above. To this day, she still has difficulty talking about the images of eternal damnation with which she was raised, and now seeks to rehabilitate similarly affected children.

Richard Dawkins notes that Douglas Adams converted from Agnosticism to Atheism through their interactions, so Dawkins knows of at least one successful convert through his work. I would like to add myself to the list of converts as well. Formerly a believer that there was something, I see now how unproductive such belief is and how unnecessary.

Douglas Adams once said, “Isn’t it enough to see that a garden is beautiful without having to believe that there are fairies at the bottom of it too?” We live in a spectacular world that only gets more interesting the more we explore it. Isn’t that enough?

Comments

2 responses to “Review of Richard Dawkin’s “The God Delusion””